Pictet: South American rumbles

There are interesting developments for investors afoot in Argentina and Brazil. Here is what Adriana Cristea, Macro Strategist, and Guido Chamorro, Co-Head EM Hard Currency Debt at Pictet AM found during their latest visits.

09.05.2019 | 14:04 Uhr

Two sides of the falls

Iguacu Falls, which separate Brazil and Argentina, may be among the most dramatic wonders of the natural world. But the roar of 400,000 gallons of water crashing against rocks per second is a mere rumble compared to economic developments currently thundering on either side of the border. Two members of our emerging markets debt team recently did some on the ground research in both countries – Guido Chamorro in Argentina and Adriana Cristea in Brazil.

These trips go beyond a run of meetings with central bankers and government officials. With the help of our partners at EMpower, a foundation that supports youth charities, we venture into local neighbourhoods, the favelas and barrios, looking for signs that official programmes are making a difference across these economies. We think this active, involved approach makes us better and more responsible investors.

What we found is reflected in our positioning. We're overweight the Argentine peso and Argentinian US dollar sovereign bonds and have a small overweight to the Brazilian real, awaiting developments to potentially build on this position and possibly move overweight Brazilian local rates.

Argentina - Guido Chamorro

Six months ago, when I last visited, the country was code red. The economy was shrinking fast, inflation was rocketing and, with observers questioning whether the International Monetary Fund’s USD50 billion in promised loans would come quickly enough, there was a growing risk that Argentina would struggle to refinance its debt.

Notwithstanding the market turmoil since, the worst seems over. In fact, during my latest trip a few weeks ago, I saw enough to be encouraged. True, the economy took a big hit last year, but it’s now showing signs of life, growing 0.5 per cent on the quarter during the first three months of the year. And refinancing risk has diminished after the IMF increased its loan by USD7 billion and brought forward disbursements.

Argentina could prove to be the make or break trade for emerging market investors in 2019. We think the country’s debt presents attractive opportunities. Its dollar denominated bonds offer good yields in the context of low upcoming refinancing risks. The local currency bonds are sure to give investors a rough ride, but for those with a strong stomach and a clear head they can generate big returns.

Still, these hopeful signs are mitigated by worryingly high inflation and significant political uncertainty.

Deceptive appearances

Spending time in Buenos Aires’ most elegant districts, it’d be easy to miss the fact that Argentina’s economy has been struggling. International flights to the capital are full as is the Four Seasons hotel. Nice restaurants are booked solid through the week. The wealthy have clearly managed to insulate themselves from the crisis by converting their savings into dollars.

It is a different story for the rest of the population. After a strong start to 2018, the economy contracted by an annual 4 per cent during the second quarter and another 3.5 per cent in the third. Inflation has been rampant.

But thanks to the biggest loan programme in the IMF’s history, things are now looking better. Wages have started to catch up to prices and sentiment is stabilising. A good soy harvest could further boost growth, which is to say there’s scope for upside surprises. Indeed, the IMF’s representative was positively surprised by how quickly the economy’s stabilised, even if inflation remains disappointing.

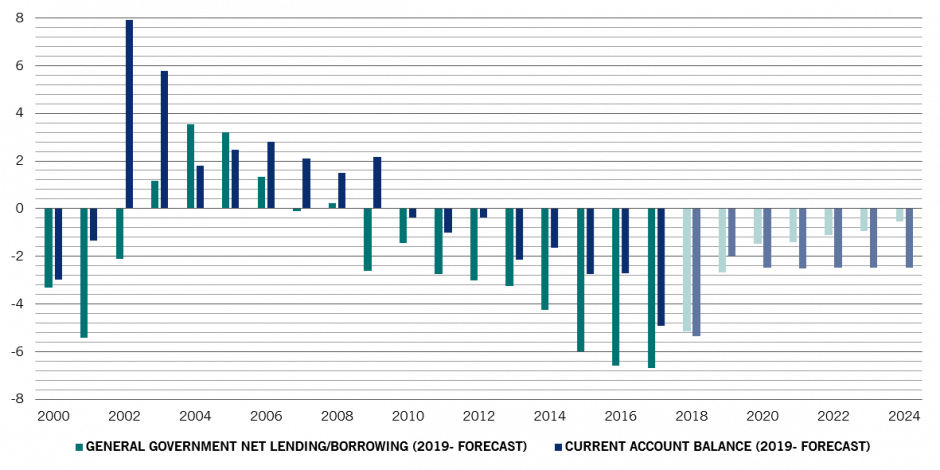

GETTING BETTER

General government budget balance and current account balance, % of GDP (forecast from 2019)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook April 2019.

Inflation has been hovering around 50 per cent – though the Starbucks coffee I had on this trip was 50 per cent more expensive than it was only last October. The IMF has upped its forecast for the current year to 30 per cent from 20 per cent. Thankfully, the IMF are blaming structural problems rather than the country’s authorities. The relationship between the IMF and Argentina seems quite strong, but it has to be. It’ll be a long time before Argentina pays back its loans.

For their part, average Argentinians are still wary of the IMF, which many still blame for the 2001 default and economic crisis. The IMF’s representatives argue that its approach has changed and it has gone to great lengths to emphasise principles such as social cohesion, gender equality and protecting society’s most vulnerable. As its head, Christine Lagarde, says, “this is not your grandmother’s IMF.”

October revolution?

The market’s big worry is what happens in October’s presidential elections. For now, it’s an open race between several candidates including Mauricio Macri, the country’s market-friendly incumbent, Cristina Kirchner, the Peronist and anti-market former president. Recent market volatility suggest Kirchner is gaining ground, though I think Macri or another candidate from his coalition still has the upper hand and a 60 to 70 per cent probability of winning.

Kirchner polarises voters, but with the Peronist party machine behind her, which includes a strong natural constituency, it would be a mistake to write her off. A Peronist compromise – and potentially less toxic outcome for the markets than Kirchner – could come from among former ministers.

ESG

As useful as it is to spend time talking to politicians and central bankers in polished Buenos Aires boardrooms, we look at how life is for ordinary Argentinians. To that end, we’ve developed a relationship with EMpower, a foundation that helps to support local charities and organisations devoted to helping young people. Our contacts confirmed that the Macri administration has been increasing social spending, though they also questioned the efficacy of these efforts. Worryingly, they also flagged up the gradual deterioration of the Argentine education system over the past decade – something that could ultimately prove a structural drag for the economy.

Where we stand

The upshot is that Argentina’s sovereign dollar-denominated bonds yielding 11 to 12 per cent should trade well if the overall hard currency universe continues to rally, but these yields are not particularly unique in emerging bond markets. Refinancing risk is very low thanks to the IMF program. We are positioned overweight, although our positive view about the overall state of the hard currency market plays a large part.

The market for local currency Argentinian bonds is much more attractive. They’re the only bonds I can think of with yields approaching 50 per cent. There’s a reason for that. The Argentine peso’s natural path is to depreciate with inflation at a pace of around 30 per cent a year, leaving investors with real returns of around 20 per cent. But the moves can be lumpy. The peso has a history of sharp 10 per cent selloffs every few months with little obvious to trigger them. So, however high the apparent yield, it’s a place where it’s easy to lose money if you get your timing even slightly wrong.

Brazil - Adriana Cristea

Complexo de Alemao is, in effect, a war zone. The favela, one of the most deprived in Rio de Janeiro, suffers extraordinary levels of violent crime in a country that already has a homicide rate at the WHO’s threshold for conflict level violence.

Yet even here there are reasons to be optimistic. For example, Alan Duarte has created a safe haven in the favela where young people can stretch themselves through sport and essential skills in a facility that overflows with children’s energy and enthusiasm. His is one of several EMpower-supported programmes I visited during my recent trip that are striving to transform Brazil from the bottom up.

But for all the efforts of Alan and his like, the politicians are still going to have to do the heavy lifting. And while the signs are positive, hopes for Brazil have to be tempered with caution.

Do new brooms sweep faster?

Brazil’s new president, Jair Bolsonaro, took office at the start of this year looking to sweep away old-style politics on the way to initiating a vast swathe of economic and social reforms. His broom’s got stuck.

A fragmented Congress and strained relationships between it and the executive government has left the government’s crucial pension reform bill languishing. Bolsonaro’s ambitions to cut pension spending by BRL1.2 trillion (USD302 billion) could well be pared back to around BRL500 billion by the time they get through (old-style) politicking. That’s a problem. We calculate Brazil needs a fiscal consolidation of around 2.5 per cent of GDP – half was to come from pension reforms, the rest from privatisation and the removal of minimum wage indexation – in order to let the economy off the leash and restore investor confidence. I estimate the government will need to generate at least BRL800 billion (USD201 billion) in pension savings to create a bullish case for the economy.

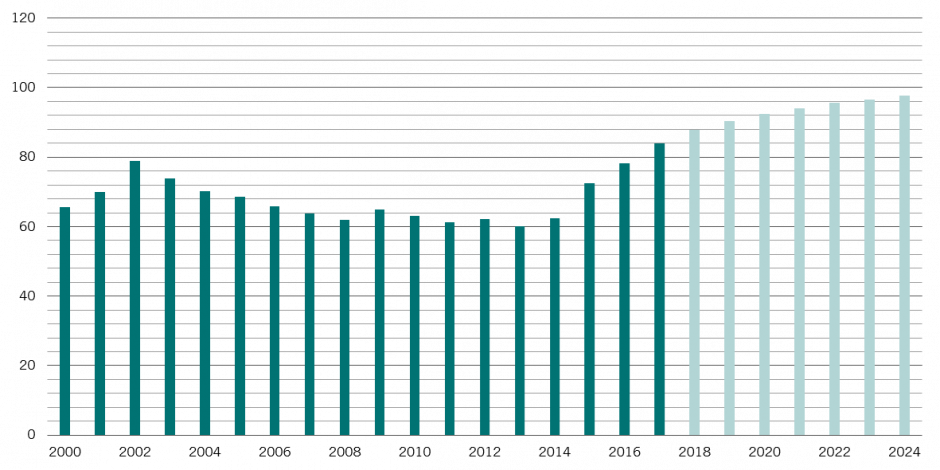

BOLSONARO'S BURDEN

Brazilian government debt to GDP, % (forecast from 2018)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook April 2019

Which helps explain why growth continues to disappoint and why, after initial enthusiasm, the mood among the Brazilian public is more downbeat, leaving Bolsonaro’s poll ratings down sharply. Consumption is muted, a consequence of a large amount of spare capacity in the labour market and slow growth in real incomes. The corporate sector, meanwhile, suffers from borrowing costs that, measured against US government bond yields, are five times higher than among Brazil’s emerging market peers. A lack of competition, bureaucracy, poor adoption of technology, an ineffective judiciary, low recovery rates all contribute to industry’s problems that can’t be resolved by official rate cuts.

Reform-minded

Should Bolsonaro manage to push through pension reforms, the rest of his agenda should be plainer sailing – most of it doesn’t need Congress’ approval. With that caveat in mind, the opening up of trade by reducing tariffs, boosting competition in various industries, privatisations, tax reform, labour reform should all be positive for the economy. Indeed, government technocrats I met seemed energised, with a strong sense that they have a mandate to implement the sort of structural changes that will create a fairer, more open and productive Brazil. There is undoubtedly a way to go. Take education. Even though Brazil spends far more on each student than similar emerging economies, schools in disadvantaged communities are crowded and a lack of local security means children get at best 80 days in the classroom a year. Efforts to improve local policing have not been very successful. But the community workers we've spoken to are worried Bolsonaro's proposed agressive intervention will only make things worse.

For now, foreign investors are right to be cautious. Flows suggest they aren’t heavily invested in the country’s bonds or currency. I feel that though the country’s prospects look better than they did, and we might be past some of the worst of the political strains, much hangs on how the pension reform negotiations progress and just how far the proposed cuts are watered down. We currently have a small overweight to the Brazilian real, favourable developments in pension reforms would encourage us to build on this position and possibly move to an overweight in Brazilian local currency bonds.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: