Janus Henderson: China - variable interest entities

In the sixth module of Janus Henderson’s study on China investing, we look at the use of Variable Interest Entity structures in China and how an understanding of the key differences between these structures can help investors accurately assess the associated risks.

19.11.2018 | 09:17 Uhr

The mountain is high and the emperor is far away – Chinese proverb

Rules from the capital are very difficult to enforce in the provinces

As discussed in the last article in this series (‘Module 5 - stakeholder relations’) a recurring theme for China, as it moves from a centrally planned economy to one where market forces are brought into play, has been the implementation of policies and regulations that bolster certain core areas of the economy and insulate key Chinese ‘industry leaders’ from foreign competition.

One aspect of this development strategy is the ‘Catalogue of Industries for Guiding Foreign Investment’, which restricts foreign investment in certain industries. Sectors included on the ‘Negative List’, such as ‘value-added telecommunication services’ or strategic ‘extractive industries’, have stringent restrictions on foreign equity ownership. Conversely, those placed in the ‘encouraged category’ enjoy preferential treatment for attracting foreign investment as a means for building capacity. Many Chinese businesses placed on the ‘Negative List’ nevertheless wish to gain the capital and prestige that comes from a foreign listing, and this has led to the widespread use of a structure called a ‘Variable Interest Entity,’ or ‘VIE’, which is intended to circumvent the regulations.

Scale of use

A VIE comprises a legal structure whereby a controlling interest, rather than being established through the ownership of the equity or holding of majority voting rights, is established instead by a set of contracts that make the relevant counterparty the primary economic beneficiary of the company’s activities.

The arrangements also typically include other contracts, which buttress these rights, including a pledge over the equity and powers of attorney over certain aspects of control. Chinese companies using VIE structures include some of the most high profile, large cap stocks in the world including Alibaba, Tencent, Netease, Sina, JD.com and Baidu, which represent more than a trillion US dollars of market capitalisation.

Origin of the structure

After the collapse of Enron, which was caused in part by off-balance sheet financing that had not been reflected in the consolidated accounts, the Federal Accounting Standards Board issued a new ‘interpretation’ called FIN46. This interpretation requires consolidation of assets, liabilities and results based on a concept of control that is broader than legal ownership, instead focusing on a company’s economic exposure to another entity. Chinese companies have used these regulations to consolidate the results of Chinese operating companies into foreign-invested holding companies as a route to accessing foreign capital, even though the offshore entities do not own the equity in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) operating companies. By using these structures, Chinese companies operating in industry sectors situated on the Negative List have circumvented the restrictions on foreign equity ownership and raised capital on the global equity markets.

How it works

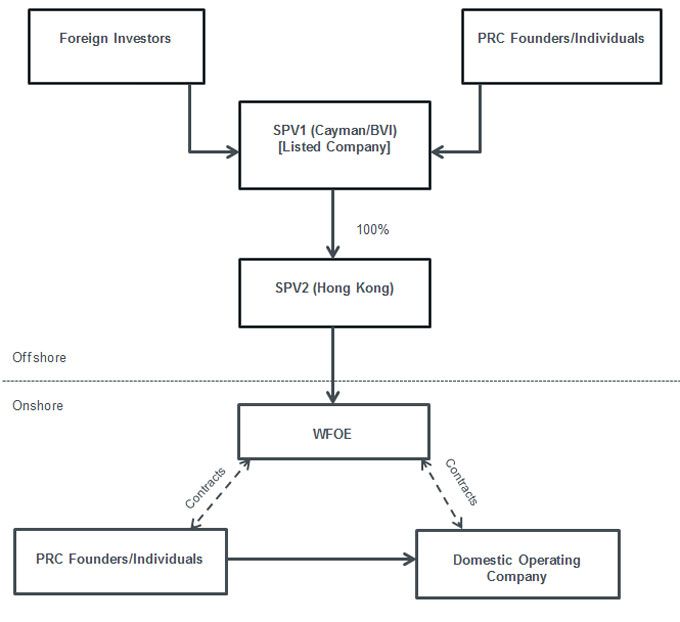

Typically, the arrangements consist of the establishment of a ‘Wholly Foreign-Owned Enterprise’ (WFOE) in the PRC in which the foreign investors own equity via the listed entity. The WFOE is a special purpose vehicle which exists for no other reason than to enter into a series of contracts with the PRC operating subsidiaries that actually conduct the company’s business activities. These contracts, which typically also include loan and service agreements, establish the WFOE (and hence the listed holding company) as the primary economic beneficiary, which means they should consolidate and – at least in theory – be able to extract the earnings offshore. A simplified VIE structure can be illustrated as follows:

Though the design of these structures shows an admirable ingenuity, there are a number of legal and practical problems that could create risks for the foreign shareholders.

Practical issues related to the VIE structure

In China, there is no equivalent of a company ‘share certificate.’ Definitive evidence of share ownership is conferred by the company’s ‘business license,’ which is issued by the local branch of the State Administration of Industry and Commerce (‘SAIC’). In order for any change in shareholdings to become effective, the SAIC must issue an amended business licence. It goes without saying that the SAIC would not issue any business licence that contravened PRC regulations, so it is unrealistic to expect the SAIC to recognise the foreign ownership of a Chinese company whose activities are situated on the Negative List.

Another difficulty arises from the requirement (explained in our earlier article ‘Rationale and methodology: risk, with Chinese characteristics’) for all corporate action to be validated by the individual acting as the company’s legal representative, with both a physical signature and the affixing of the company ‘chop.’ Registration of the change in shareholders at the local branch of SAIC requires these actions, so VIE arrangements can be thrown into disarray if a dispute arises between the legal representative in China and the Board of the offshore entity. There are many examples of an aggrieved legal representative effectively holding a company to ransom by refusing to file documents effecting corporate action and withholding the ‘chop’.

Legal issues relating to the VIE structure

Article 52 of the PRC Contract Law states that any contract entered into in order to ‘conceal an illegal purpose under the guise of a legitimate transaction’ is technically void. Hence, according to this law, VIE contracts, which are intended to circumvent the ‘Catalogues of Industries for Guiding Foreign Investment’, may simply be legally invalid as well as unenforceable in practice.

The case of Alipay

VIEs have long occupied a legal grey area and, while the associated risks were disclosed in the various prospectuses for foreign offerings involving VIEs, they have not been explicitly challenged by the Chinese state.

The most high profile case concerning a VIE structure involved Alibaba and its major shareholder, Yahoo! The China Banking Regulatory Commission declined a licence for banking activities for Alipay, the online payment service provider connected to Alibaba via a VIE, as long as it remained foreign-invested. Jack Ma, the Chief Executive Officer of Alibaba, argued that he had no alternative but to sever the VIE between Alibaba and AliPay, which was considered a crown jewel of the Alibaba Group, and executed the termination of the VIE in his capacity as legal representative for both the WFOE and the VIE, so that the results of Alipay were no longer being consolidated into the financial statements of Alibaba.

The subsequent legal dispute between Alibaba’s shareholders, including Ma, Yahoo! and Softbank, eventually led to a settlement whereby Alibaba Group indirectly gained from future appreciation in the value of AliPay but retained no control over it. While this episode was eventually resolved through a negotiation, it illustrates the ease with which a very significant VIE arrangement can be extinguished by the unilateral act of the legal representative.

2017 catalogue

Although VIE structures have by and large been afforded some degree of tacit consent from the Chinese state, in 2017 the government published legislation which explicitly acknowledged the existence of VIE structures for the first time. The 2017 amendment to the ‘Catalogue on Foreign Investment’ introduced the concept of an ‘actual controlling shareholder’ of a foreign-listed Chinese company.

The updated rules require that any PRC entity that has attained an overseas listing by use of the VIE structure must have as its ‘actual controlling shareholder’ a PRC citizen. Hence, only foreign-invested entities that are effectively controlled by Chinese nationals will be treated as Chinese companies when applying for market entry licenses to operate in restricted industry sectors.

What’s next?

After years of watching tech giants and other Chinese behemoths raise overseas financing at the expense of domestic markets, China has begun considering policies designed to attract its large-cap companies back to the mainland, thus avoiding the leakage of value out of China.

Recently, the China Securities and Regulation Committee has been assessing the potential viability of ‘Chinese Depositary Receipts’ (CDRs), which would allow the trading of foreign-listed Chinese companies’ shares on domestic exchanges. Modelled on the American Depositary Receipt, CDRs would present a new trillion-dollar investment market and would transform not just the market capitalisations of some of the largest tech companies in the world, but would also transform the competition between China’s domestic exchanges and other well-established bourses. How future regulations on CDRs will affect the rules concerning VIEs is, at present, unclear.

Nevertheless, investors may be able to anticipate VIE risk better through a thorough understanding of the limitations on the enforceability of these contracts and assessment of the other procedures put in place to protect foreign investors.

Key considerations

The table below illustrates the factors that we believe can best help investors accurately assess the risk inherent in a VIE structure.

| Higher Risk | Lower Risk |

|---|---|

| Asset-heavy VIEs: majority of company’s assets and operations held and conducted in the onshore VIEs. | Asset-light VIEs: majority of the assets held in WFOES; VIEs only hold business licenses. |

| Misalignment of interests: the legal rep and equity owners of the VIEs do not have substantial stakes in the offshore-listed holding company. | Alignment of interests: the legal rep and equity owners of VIEs derive the majority of their economic interest from shares in the offshore-listed holding company. |

| The VIE’s ‘chops’ are either in an unknown location or in the sole possession of the VIE’s legal rep. | The VIE’s ‘chops’ are lodged at an independent third-party, such as a law firm. |

| Board composition of VIE does not match diversity/skill of the offshore-listed holding company. | Diversity and skills of the VIE’s board reflects that of the offshore-listed holding company. |

| Unclear whether VIE contracts are officially registered with relevant bureaux; lack of power of attorney. | All the supporting VIE contracts are officially registered with the relevant bureaux; contracts include a power of attorney. |

Investment team perspective

Andrew Gillan, Head of Asia ex Japan Equities:

"It is difficult for investors to gain exposure to China's fast growing and new economy sectors without tolerating VIE structures. At the end of the day, it comes down to trust and analysing how these companies have behaved in the past."

Part 1: Janus Henderson: China investing - China-specific risk

Part 2: Janus Henderson: Risk, with Chinese characteristics

Part 3: Janus Henderson: China investing - financial ratios

Part 4: Janus Henderson: China investing - board oversight

Part 5: Janus Henderson: China investing - material and related-party transactions

Diesen Beitrag teilen: