BNP Paribas: Understanding Investment Opportunities in Chinese Equities

China’s economic development is a unique success story. With 1.4 billion inhabitants and a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of USD 12.8 trillion in 2017, China is today the world’s second largest economy after the United States, and is increasingly playing an influential role in the global economy.

26.06.2018 | 13:19 Uhr

In the special “Wonderful China: Understanding Investment Opportunities in Chinese Equities” report, you will discover:

- The structural case for China

- China’s macroeconomic outlook for investment

- Three structural trends driving long-term investment opportunities in China

- Green China: Wait... Is China the leader in green investments?

Click here to read the full report

The changing dynamics of chinas risks

by Chi Lo, Senior Economist greater China

Concerns about China’s risks have largely receded after a solid economic performance in 2017.

What about this year? Hidden behind an expected slowdown in real GDP growth this year are the same old set of risks stemming from potential policy missteps due to the push for debt-reduction, property bubble crackdown and enforcement of environmental standards, and from trade friction with the US. However, the dynamics of these risks have changed recently, affecting the probability of the outcomes in the coming year.

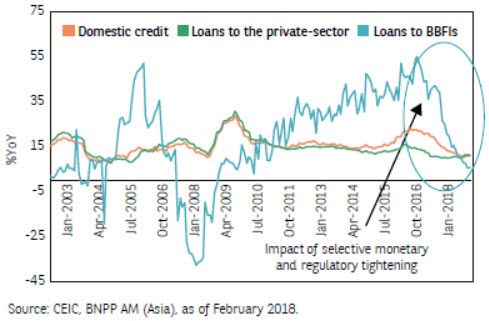

Chart 1: Selective deleveraging also slows total credit growth

Over-tightening risk ebbs and flows

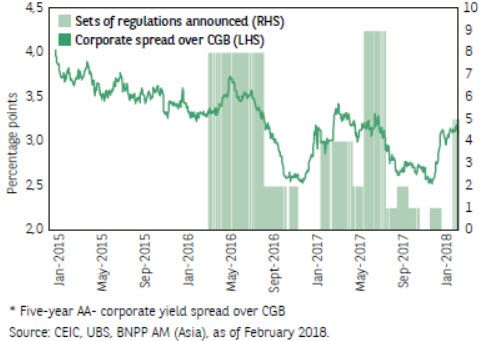

The risk of over-tightening of financialregulation leading to unintendedconsequences of credit events wasincreasing early in the year but hasrecently stabilised due to the PBoC’spolicy shift towards an easing bias inApril. Beijing started its battle againstfinancial risk in early 2017 by implementingselective tightening to forcedeleveraging in the wholesale fundingmarket and non-bank financial institution(NBFI) sector. The impact was feltthroughout the system with total creditgrowth declining (Chart 1) and corporatebond yield spread rising (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Corporate bond spread* and new regulations announced

Nevertheless, the authorities stillmanaged to wage that battle withoutcausing collateral damage to the realeconomy. Real GDP grew by 6.9% YoYin 2017, above the government’s targetand market expectation of 6.5%. Controllingsystemic risk remains a highpolicy priority in 2018. The renewal oftightening measures in October 2017,after a four-month pause, shows thatBeijing was confident in speeding up itsdeleveraging efforts..

In addition to continuing cracking down on unconventional credit channels of shadow banks and NBFIs, the regulators are now stepping up scrutiny on conventional channels of credit, including trust loans and entrusted loans, which together account for about 13% of aggregate financing. They also want to reduce household leverage, which is predominately mortgage.

Mortgages account for about 18% of bank loans and bank loans account for 70% of aggregate financing. So mortgage lending is about 13% of aggregate financing. This means that Beijing’s new deleveraging effort is expected to hit 26% (13% of trust and entrusted loans + 13% of mortgage loans) of aggregate financing this year. Adding it to the 16% share of the NBFI loans in domestic credit that are already being targeted for debt-reduction, we would expect 42% of aggregate financing to come under deleveraging pressure this year.

This would put a large liquidity squeeze on the system. The regulators will have to allow some offset to lessen the potential growth damage and systemic risk. In my view, this may come in the form of Beijing allowing more bond issuance by the corporate and provincial government sectors to keep aggregate financing growth sufficient to sustain 6%+ GDP growth. So expect an increase in bond supply to put upward pressure on the onshore yield spread further this year.

Furthermore, the deepening of deleveraging efforts will increase the number of defaults, leading to credit differentiation by investors and contributing to widening of credit spread in China. But the PBoC has also stepped up its effort to ensure no systemic risk will result. In April, it shifted to a policy easing bias and cut the bank reserve requirement ratio by 100 bps, releasing about RMB1.3 trn of liquidity into the system to contain the potential damages of deleveraging on GDP growth.

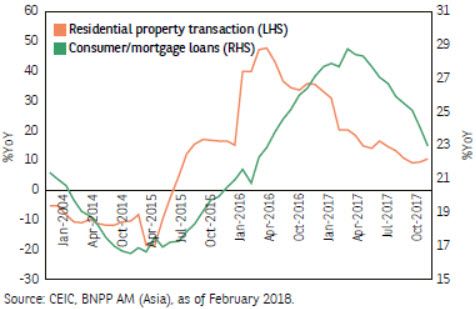

Property market risk is decreasing

Restrictive property market policies over the past few years have led to a slowdown in mortgage loan growth and property transactions (Chart 3). Further cooling of the property market is expected for 2018. But with inventory declining gradually and demand from smaller cities reviving, the risk of a property market crash is decreasing.

Chart 3: Housing market continues to cool

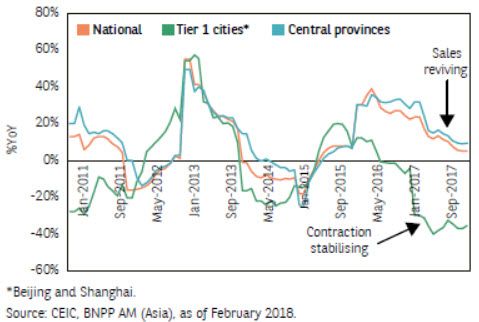

Furthermore, Beijing has shown sensitivity towards the potential damages of its hawkish property policies on economic growth. Some non-Tier-1 cities have loosened their housing policies in recent months, which helps revive property sales in the central provinces and stabilise the volume contraction in the Tier-1 cities (Chart 4). So the risk of a policy misstep crashing the property market is also decreasing.

Chart 4: Residential property sales volume

Stringent environmental standards risk is stabilising

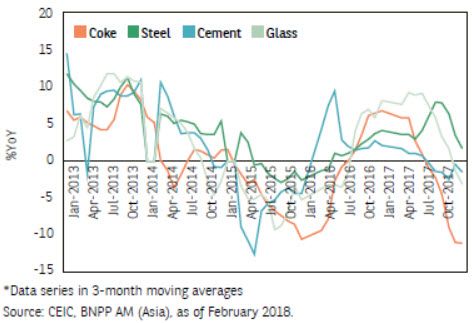

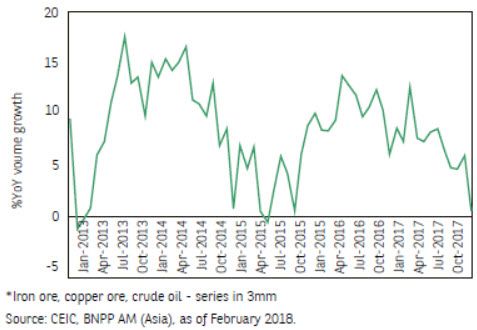

Beijing started enforcing stringent environmental standards by putting tight restrictions on the heavy and polluting industries, such as steel, cement, glass and coke, since 2017. The impact has been an improvement in air quality at the expense of a sharp decline in the heavy industrial output (Chart 5). Even commodity imports have plunged (Chart 6), reflecting the contraction in the heavy industries.

Chart 5: Heavy industral output* dropping sharply on enforcement of environmental standards

Yet the damage to overall GDP growth has been contained. This is partly because the air-pollution curbs are focused on north China but output in the south has increased to provide some offset, and partly because Beijing has scaled back the environmental crackdown, reflecting its awareness of the campaign’s collateral damage on the people.

Chart 6: Commodity imports* plunge

In fighting air pollution, the authorities moved to establish a coal-free zone around Beijing late last year by forcing households to switch from coal to electric or natural gas heating.

But the local officials pushed ahead too hastily without sufficient electricity and natural gas supply to support the switch, leaving thousands of families, hospitals and schools without heating in the frigid winter. After a public outcry that caught national attention, the central authorities ordered a pause of the programme until sufficient facilities are installed. The switching from coal heating to electric or natural gas will continue but the completion deadline has been postponed to the end of 2019.

Policy sensitivity and cyclical recovery of some of the heavy industries suggest that the maximum stress of over-zealous enforcement of environment standards damaging growth may be behind us. The risk of a policy mistake in this regard is stabilising.

Sino-US trade friction risk is rising

This is in fact a political risk that is outside of Beijing’s control. But the persistent Sino-US trade surplus is an acute problem that US President Trump will use to harden his hawkish trade policy on China, partly to divert attention from the ongoing “Russia gate” investigation and partly to shore up support ahead of the mid-term elections later this year. So expect more trade frictions between the US and China as the year wears on.

Nonetheless, the macroeconomic effect of Sino-US trade friction on China is not too worrisome because there are vested interests in both countries to resist harsh trade sanctions. Market research also shows that even a permanent 10% fall in Chinese exports to the US would only cut about 0.3ppt from China’s GDP growth a year, but this impact can easily be offset by Chinese domestic spending or exports to other destinations for example via the Belt and Road initiative. So the impact is likely to be more on individual sectors. While the odds for this risk to materialise are rising, it is not a big one for China.

Overall, the risks to China’s outlook this year appear to be within manageable limits. A potential black swan may be the geopolitical risks which are scattered throughout Asia and surrounding China (the East China Sea, the South China Sea, the Korean Peninsula and the China-India-Pakistan borders).

In the special “Wonderful China: Understanding Investment Opportunities in Chinese Equities” report, you will discover:

- The structural case for China

- China’s macroeconomic outlook for investment

- Three structural trends driving long-term investment opportunities in China

- Green China: Wait... Is China the leader in green investments?

Click here to read the full report

Diesen Beitrag teilen: