Schroders: Climate change matters: a roundup of events in June

In this monthly newsletter, the ESG team reviews recent climate change-related developments.

22.07.2015 | 15:29 Uhr

Hottest May in 136 years

The regularity with which global average temperatures are being broken is at risk of making the news that this May was the hottest May on record for 136 years, fade into the background. However, the consequences of these rising temperatures are likely to make the news much more frequently, and sadly the sustained, fatal heat waves in both India and Pakistan are examples of this. The frequency and severity of these types of extreme weather events are expected to increase with continued global warming. One 2013 study shows that in some cases, extreme heat events are already ten times more likely to occur due to current cumulative impacts of anthropogenic global warming.

Pope encourages action

In the face of the observed impact of climate change and the lack of sufficient political action, the Pope, leader of the 1.2 billion members of the Roman Catholic Church, recently issued a rare Papal encyclical on climate change in order to end theological debate on the issue and encourage action. Within the encyclical he conveys four main points:

- That we have a moral obligation to take care of the earth and the poor

- That humanity must own up to the fact that it is driving the bulk of observed global warming

- That overconsumption by western society has a disproportionate effect on the poor who do not get the benefits of that way of life

- That society must take urgent global action to reduce carbon dioxide emissions within the next few years to prevent climate change becoming a compounding crisis on future generations.

Dutch climate change policy illegal

It wasn’t just the moral arguments being put forward this month. In Holland, a court ruled that the Dutch government’s current climate policy is knowingly contributing to a breach of the target to keep global warming to within 2 degrees Celcius of pre-industrial temperatures (a target that global governments have signed up to). As such, the court ruled that under human rights and tort law, the Dutch climate policy was illegal and the Dutch government was ordered to cut its emissions by at least 25% within five years (the current plan is for a 14-17% reduction by 2020).

Rising costs of climate change

Over the last few years we have seen an increasing realisation that climate change will have economic consequences. This month saw the US Environmental Protection Agency release a report which finds that, in the absence of action to curb greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, climate change could cost the US economy up to $200 billion by the end of the century. Perhaps, more important from an investor’s perspective, were the findings of a survey examining how corporations are addressing climate change. The research found that two thirds of respondents were concerned about the increased operational and capital costs associated with climate change with 25% saying climate change was already impacting on operational costs.

The costs of climate change cannot just be calculated in economic terms though. A report produced by the Lancet and the University College of London’s Institute of Global Health concluded that on a business-as-usual emissions path, the impacts of climate change on human health and survival are potentially catastrophic and could undermine all of the last 50 years’ progress on global health. The report also finds that the benefits to health from slashing fossil fuel use (such as reduced air pollution), are so large that tackling global warming also presents the greatest global opportunity to improve people’s health in the 21st century. It concludes that political will is now the major barrier to delivering a low-carbon economy and the associated improvements to health and poverty, not finance or technology.

China’s ambitious decarbonisation rate

At the end of June, China, the world’s largest emitter of GHGs, submitted its reduction plans ahead of the international climate change negotiations in December (COP21). China has extended its previous ambition to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by 40-45% on 2005 levels by 2020, to a 60-65% reduction by 2030. China’s target implies an annual decarbonisation rate of 4% per year from 2005 to 2030, a rate which exceeds those of both the US and Europe.

The end of the fossil fuel era?

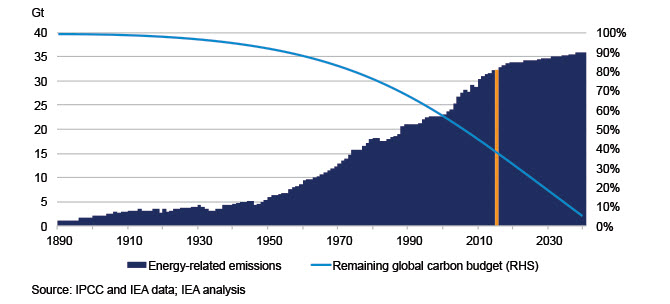

In addition to China’s ambitious targets, the G7 (which met this month) recognised, for the first time, the need to decarbonise the global economy over the course of this century and to achieve the upper end of a 40-70% reduction in global GHG emissions by 2050. Whilst this statement is encouraging, it will need to be followed up by stronger political commitment, as current commitments imply that emissions will continue to grow (see Figure 1). The G7 declaration also reaffirmed its 2010 pledge to mobilise $100 billion a year by 2020 to help poor nations adapt to climate change. However, Brazil, China, India and South Africa, in a joint statement, voiced their disappointment that to date financing has fallen short by $70 billion. We believe this statement serves as a warning signal ahead of COP21, as this issue has been a sticking point at previous negotiations.

Figure 1: Current emissions will continue to grow unless they are met with stronger political commitment

Taken from “Energy and Climate Change, World Energy Outlook Special report”, International Energy Agency, June 2015. Note IPCC stands for International Panel on Climate Change.

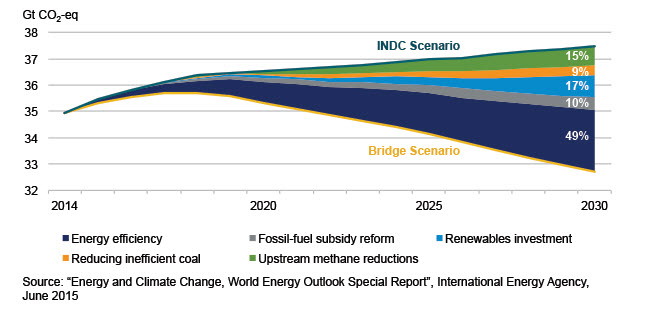

How to decarbonise the economy

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) latest report has produced analysis (see Figure 2) which shows the ways in which countries could decarbonise their economies. Their suggestions are:

- Phase out energy inefficient equipment, appliances and buildings;

- Ban the construction of new inefficient sub-critical coal power stations and progressively reduce the use of the existing ones;

- Phase out fossil fuel subsidies by 2030;

- Reduce methane leaks in oil and gas production; and

- Increase global investment from $270 billion currently to $400 billion by 2030.

Figure 2: Ways in which countries can help contribute to keeping global warming under 2 degrees Celcius

Note that INDC stands for Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, which represent countries’ climate change commitments ahead of climate change negotiations that are due to be held in December.

Limited political will now means bigger emission cuts later

However, despite the moral, human development, economic and legal arguments, we don’t believe that there is the political will for the implementation of these recommendations ahead of COP21. This implies that (unless politicians are completely willing to disregard scientific consensus in favour of short-term interests) there will have to be a significant ratcheting up of political commitment post 2020 and we would expect this to be addressed at COP21 in December.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: