Janus Henderson: US Libor rate rising again

The 3-month US Libor—OIS spread has risen sharply over recent months and is now close to the widest levels seen in the eurozone debt crisis. Mitul Patel, Head of Interest Rates at Janus Henderson, explains.

19.03.2018 | 09:45 Uhr

The past few months have seen a dramatic move up in 3-month US Libor, especially relative to the 3-month overnight index swap or OIS.

The past few months have seen a dramatic move up in 3-month US Libor, especially relative to the 3-month overnight index swap or OIS.

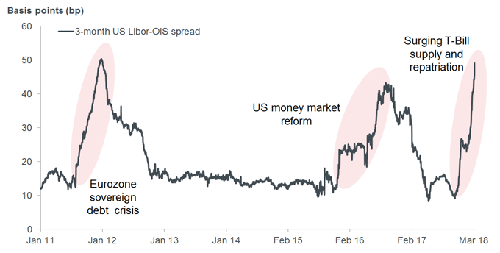

As the chart shows, the spread has moved sharply over the past three months, moving from its lows around 10 basis points (bp) to levels not seen since the eurozone sovereign debt crisis.

US Libor-OIS spread rising significantly

(Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, 3-month US Libor—overnight index swap (OIS) spread, daily data, as at 16 March 2018)

What has caused the move and should investors be worried?

Libor (London interbank offered rate) is an unsecured lending rate used by banks to lend funds to each other over different periods such, as 1, 3 or 6-months. OIS is an interest rate swap based on the overnight unsecured lending rate for bank borrowing. In the US, this is the overnight Fed Funds rate, which is compounded for the relevant period.

Historically, moves in Libor-OIS spreads have been a symptom of stress in the banking system, as banks become unwilling to take counterparty credit risk, even for very short periods of time. Thus the 3-month US Libor-OIS spread has come to be used by investors as an indicator of liquidity risk, in turn a reflection of credit risk.

We first saw large moves around the Global Financial Crisis, as there was a reluctance to lend to banks without knowing their true exposure to sub prime assets. Having then settled down, the escalating eurozone sovereign debt crisis saw the spread move significantly wider as European banks struggled to get funding. The spread contracted back to low levels until US money market fund reforms in 2016 pushed it higher, when these funds switched their holdings to Treasury bills (T-bills) and away from corporate paper and certificates of deposit. It then reverted to its lowest levels — until a few months ago.

Banks are not to blame this time

The past three months have seen the spread widen again significantly. This time, however, the moves have not been associated with stresses in the banking sector. In fact, bank credit spreads have been immune to moves in money market spreads. The recent move in Libor rates has also coincided with a concurrent cheapening in 3-month US T-bills relative to OIS, suggesting that the large increase in T-bill issuance is to blame for the move.

Following the suspension of the debt limit, the US Treasury has increased the amount of bill issuance dramatically, with net sales over the past five weeks exceeding net bill supply in 2017 by over two times. Money market funds and dealers also appear to have positioned defensively amid the pick-up in supply, contributing to the spread widening.

The market currently expects T-bill issuance to decrease in Q2, though there is a risk that investors are currently too sanguine about this issue and that Libor-OIS spreads do not contract back to their historically tight levels.

Although bill issuance is likely to decline somewhat into Q2, fiscal deficits are projected to stay elevated for several years and the Treasury is not planning to increase the weighted average maturity of issuance, so T-bill issuance is likely to remain a key part of funding the deficit in the future.

Surge in T-bill issuance is not the only culprit

Recent tax changes have incentivised corporates to repatriate cash back to the US, which will most likely be used to pay tax bills, invest and conduct buybacks. Previously this money would have been parked in money market instruments, so diminished demand for money market instruments has exacerbated the issue.

Finally, unwinding the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet will drain excess reserves and reduce the cash available to invest in bill instruments.

Knock-on implications

Although the causes of the recent move in the Libor-OIS spread do not suggest any imminent risks around the banking sector, they may have knock-on implications that investors should consider.

The moves in the Libor-OIS spread may be a symptom of the public sector ‘crowding out’ private sector borrowing — the increase in public sector borrowing is leading to higher borrowing costs for the private sector. With US household savings rates low and corporates also increasing their leverage, the US government may struggle to fund its deficits domestically.

With low levels of domestic savings and the economy at close to full employment, higher fiscal deficits may merely lead to higher current account deficits. This may result in some disappointment over growth in the US compared to current elevated expectations. Public sector borrowing may also crowd out money that would have gone into risk assets, potentially placing pressure on valuations in equity and credit markets.

A final thought

The volatility of Libor-OIS spreads also challenge the long-term viability of Libor. Announcements from the Alternative Reference Rate Committee (ARRC) over recent weeks suggest the US market is likely to move towards a Secured Overnight Funding Rate (SOFR) as its replacement rate for Libor. Regulatory bodies globally are continuing to push for substitutes and while it is likely to take several years to fully adopt alternatives, recent moves in the Libor-OIS spread serve to remind investors of the risks around using Libor as a reference rate.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: