NN IP: Powell to market - I hear you!

Navigating cross-currents and managing market expectations are two challenges for the Fed.

11.01.2019 | 09:15 Uhr

The global economy seems to have arrived at some kind of crossroads where the big question is which set of forces will ultimately prove to be the dominant. On the one hand, the trade and industrial data fairly consistently surprised on the downside last year as this part of the economy was battered by rising protectionist risks, the underlying slowdown in Chinese growth and a host of highly impactful one-off shocks in Europe and Japan. Meanwhile, other political risks (Italy, Brexit, yellow vest movement) have moved towards the forefront and the whole mix clearly became the focal point of market worries in the last quarter. On the other hand, the US and Japanese domestic economies continued to hold up pretty well throughout this period. Last Friday’s blockbuster US payroll report, which signalled very robust nominal labour income growth as well as a further increase in labour supply, is just one example. In Japan, the business surveys generally remain well above their long-term averages and investment intentions are still strong, in part because the overheating economy gives businesses an incentive to invest in labour-saving technology. Even in Euroland, consumer spending seemed to hold up pretty well last autumn. And while the outlook for capex is a bit murkier, one could argue that the economy should be growing above potential provided these downside risks abate.

However, the most important change in the past quarter was that markets started predominantly focusing on the downside risks which produced a severe tightening of financial conditions. For the global economy as whole, the tightening seen so far will largely be offset by more fiscal stimulus in China and Euroland. Nevertheless, it is clear that the base case should now be that global growth will proceed at a somewhat slower pace this year compared to 2018, and that the risks are tilted to the downside. The future evolution of financial conditions and private sector confidence will crucially determine to what extent these risks will manifest. Meanwhile, a very important driver behind both will be the outcome of the trade talks between the US and China as well as the development in other areas of political risk.

Navigating cross-currents

Another key factor will be the reaction of central banks in developed markets. Be-cause the Bank of Japan is fully focused on yield-curve targeting, while the ECB has its back close to the monetary easing wall, the burden mostly falls on the Fed. Of course in other circumstances, markets would also be most sensitive to Fed policy for the simple reason that it acts as the most important driver of the cost of dollar funding. In this respect there were some real fireworks in the markets in late December. The press conference following the December Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decision to hike by 25 bps led to a substantial sell-off in risk assets. In light of this, it would be tempting to conclude that Fed Chairman Powell’s communication skills are not as well-honed as those of his predecessor. Indeed, we do not recall seeing large market moves on the back of Yellen’s press conferences. Powell has caused this kind of volatility twice within a very short period. First in early October, when he stated that rates were a long way from neutral and then again in December by seemingly implying that the Fed was relatively insensitive to heightened risk aversion in the market. Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that Yellen’s job was much easier because back then the policy rate was still clearly below neutral. Powell is dealing with a policy rate that is nearing the orbit of neutral in an economy where growth is set to remain above potential in the foreseeable future, and which is subject to considerable upside and downside risks (or cross-currents, as Powell called them). This makes communication much harder, especially in a market environment characterised by a large bias to focus on the downside risks and ignore the upside risks.

Both Powell and Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida had already signalled in November that the Fed has become more responsive to downside risks. In this light, the December statement seemed to strike the right balance but the market was probably looking for a stronger Fed put, which it did not get as Powell tried to navigate the various cross-currents buffeting the US economy. This created some confusion here and there. For instance, on the one hand the statement mentioned that “some further increases” in the policy rate were warranted. However, during the press conference Powell emphasised “significant uncertainty” about the path/pace and ultimate destination of the policy rate. At first glance, this appears contradictory. Our interpretation of the message Powell wanted to send is as follows: the policy rate is still slightly below the neutral zone, and the outlook for nominal growth as well as the related risks warrant the Fed taking the policy rate at least into the lower half of the neutral range. Still, as the policy rate is raised further, uncertainty about the outlook as well as the “stars” (r-star and u-star, which represent equilibrium interest and unemployment rates) warrants an increasing degree of data dependency.

Nevertheless, the main contributor to the market’s hawkish interpretation of the Fed came from its communication about balance sheet policy. In a way, this was an accident waiting to happen. Both balance sheet roll-off (quantitative tightening) and policy rate hikes are forms of tightening. Using both actively at the same time could be confusing. This is why the Fed put QT on autopilot and uses (guidance about) the policy rate as the instrument for reacting to changes in the outlook. However, the Fed has never clearly explained how one form of tightening influences the other and this mistake was essentially the reason for market confusion in late December. During the press conference, Powell seemed to hold on firmly to the autopilot story which the market interpreted as pretty hawkish. After all, following the December hike the market is not pricing any further hikes. This means that in order to send a more dovish signal that will have an impact on the market, the Fed will have to resort to either signalling rate cuts or a dovish change in balance sheet policy. But from the Fed’s perspective it still has the option of becoming more dovish by scaling down the dot plot while preserving the autopilot on QT.

Looking through different lenses

In a way, the Fed and the markets are thus looking at the world through different lenses. The Fed views the outlook for the entire US economy and the balance of related risks. Over the past three months or so, the market seems to be more focused on the downside risks stemming from subset of the entire economy, i.e., the trade/industrial part as well as how political risk impacts this. Of course, the market’s perspective matters a lot to the economy as a whole. It is clear that the downside risks have not risen over the past two months. We have always felt that the big danger in the trade story was that it would cause a deterioration in confidence and financial conditions. As far as confidence is concerned, the jury is still out on the extent to which this is happening. However, financial conditions have clearly tightened a lot. The Fed did see and acknowledge this back in mid-December but because it is viewing matters through a different lens than the market, the Fed also paid attention to the risk of further domestic overheating. Last Friday’s payroll report serves as a reminder that this risk was still very much alive and kicking in December. Hence, looking through the Fed’s lens in mid-December, it made perfect sense to bring rates closer to the neutral orbit and signal a high degree of data dependence once it is there.

From the perspective of the market’s lens, this seemed like a policy mistake. In other words, it seemed as if the Fed was determined to continue raising rates in accordance with the dot plot schedule come hell or high water. The resulting market turmoil was greatly enhanced by rumours that Trump was thinking of firing Powell. All this highlights the very complicated two-way street relationship between the Fed and the markets. Some economists feel the Fed should not be intimidated by the markets and should establish itself as the dominant player in this game as this is the only way to reduce the risk of future financial bubbles. We believe this is rather an extreme position and wonder whether monetary policy is the prime driver of bubbles in the first place. The good news is that the Fed leadership takes a more nuanced approach and, even more importantly, is willing to change course in the light of new developments. The Fed was fully justified in emphasising two-sided risk management in the second half of last year. Still, that does not alter the fact that a large and persistent tightening of financial conditions will lower r-star (the equilibrium rate of interest) and thus require less Fed tightening.

In December, NY Fed President John Williams already signalled that QT would be reconsidered in the case of a severe deterioration in the outlook. Last week Powell took this a step further by effectively saying to the market: “I hear you loud and clear”. We interpret this as a significant increase in the strength of the Fed put option. In other words, for now two-sided risk management has given way to mostly downside risk management. The clearest indication of this was that Powell explicitly used Yellen’s dovish policy turn in 2016 (four intended hikes at the start of that year and only one actual hike) as an example of good policy making. This suggests the Fed now believes the situation bears a lot of similarities to that period, particularly when it comes to external risks boomeranging back into the US economy via tighter financial conditions and the fact that Fed hikes may actually increase these external risks. In discussing the 2016 example Powell emphasized patience, a willingness to be flexible on both rates and the balance sheet, and the Fed’s readiness to change course aggressively if needed. As for the near-term outlook, he mentioned domestic strength but also that this is the rear-view mirror and the downside risks are building going forward. Importantly, Powell is not concerned about stronger wage gains and feels that muted underlying inflation gives the Fed ample scope to respond to these downside risks. He also clearly stated that this response could feature a change in balance sheet policy; i.e., the Fed will not hesitate to make adjustments to QT if this proves necessary to achieve its mandated goals.

In light of all this, we now believe the Fed will pause at least until May/June and emphasise downside risk management in the meantime. If this strategy is successful and the market regains its risk appetite the Fed will probably gradually shift back to two-sided risk management and bring rates into the neutral zone. This is why our base case should remain for two hikes this year. However, in the near term it is not likely that the market will start to price that in, all the more so because this time around the main determinant of the extent to which risk appetite returns may well be the outcome of the China-US trade talks.

Emerging markets: Fed repricing and Chinese stimulus

Following December’s high levels of financial market volatility, the start of the new year is a good time to consider where we stand with regard to emerging market growth and inflation. One of the negative drivers of global markets in the final months of the year was the deterioration of Chinese and other Asian data. The uncertainty about the future trade relationship between China and the US, coupled with doubts about the sustainability of high growth in consumer electronics worldwide, was the main factor that pushed business confidence and manufacturing investments down throughout East Asia. The December manufacturing PMI in China, which dipped below the neutral 50 mark, was particularly worrying; so too were the Korean ¬export numbers for December, which showed weakness across the board. Korean export volume growth was negative for the second month in a row.

At the same time, growth data appears more resilient and not as bad as anticipated. In some cases, it is even improving in the emerging economies that are less dependent on global trade. The countries that were under severe pressure earlier in 2018, owing to sharp capital outflows and tightening financial conditions, are now showing cautious signs of improvement. Indonesia, Brazil and Argentina are probably the best examples.

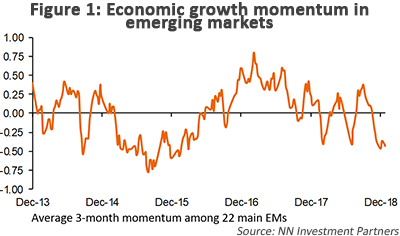

On aggregate, emerging markets still exhibit significant weakness. Our own EM growth momentum indicator is still in negative territory and remains close to a three-year low (see Figure 1). This weak starting point for the year means that our cautious growth forecast for 2019 of 4.6% will not need to be revised upwards anytime soon. Nevertheless, we see the outlook for EM growth improving somewhat. This is for two reasons: the reduced likelihood of more Fed rate hikes in the coming quarters, and the Chinese authorities’ recent announcements of increased policy stimulus.

The fact that investors no longer expect any rate hikes from the Fed in 2019 and our own view that we will not see any hikes before early summer should make us more positive about the prospects for capital flows to the emerging world and EM financial conditions. In recent months, our EM financial conditions indicator has already gradually moved from very negative to a more neutral level, on the back of Fed repricing and declining oil prices. We now expect EM financial conditions to ease in the coming months. This should create room for EM credit growth to pick up and prevent a sharp decline in EM domestic demand growth.

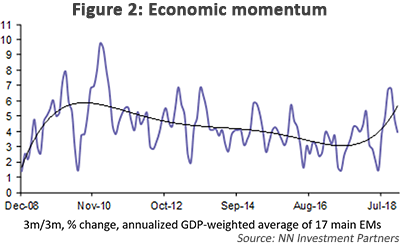

In addition to the Fed repricing, the outlook for EM inflation is a further reason why we expect easier financial conditions in EM. In 2018, inflation momentum deteriorated sharply, as a result of the increasing oil price until October and the exchange rate depreciation throughout the emerging world (see Figure 2). But the sharp decline in oil in fourth-quarter 2018 and exchange rate stability since September helped to stop the deterioration of EM inflation. In recent months, we have even seen a cautious decline in inflation again. On balance, there are still more EM central banks hiking rates than cutting rates, but this situation should change in the near term.

This brings us to China. As we have stated, concerns about global trade and Chinese growth were a key factor pushing global markets down in the final months of 2018. The Chinese authorities have been easing economic policies since the US-China trade conflict escalated. Since the summer in particular, the authorities have implemented tax cuts to stimulate household consumption and private investment growth, along with increased fiscal spending to push infrastructure investment growth higher. But until last week, there was only a modest effort to bring about a meaningful increase in credit growth. Until then, the government’s longer-term focus on maintaining financial system stability, by reducing leverage and by preventing excessive risk-taking by shadow banks, remained a priority. This now seems to have changed. Reacting to the weak data of November and December, the authorities have announced new infrastructure investment plans, particularly in railways, and they have moved towards more aggressive monetary easing. Last week, when the Chinese authorities cut the reserve requirement ratio for banks by 1 percentage point, they also put explicit pressure on banks to make use of the increased liquidity. In addition, existing bond issuance targets for local governments will be implemented earlier than previously stated, and yesterday, the authorities in Beijing announced new incentives to boost auto sales.

All this increases the likelihood of a meaningful pick-up in Chinese domestic demand growth later this year. The main question remains how successful the Chinese authorities will be in compensating the negative impact of the trade conflict on the manufacturing sector. Still, the increasing stimulus efforts should be taken into account when assessing the outlook for EM growth. So while we remain worried about the trade outlook, we believe that the prospects for EM growth have improved in recent months and particularly weeks.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: