UBS: Germany has the world’s largest current account surplus

Germany’s large and rising current account (CA) surplus features highly in global policy discussions, often leading to calls for fiscal easing to stimulate German domestic demand.

22.11.2016 | 10:24 Uhr

At around US$300 billion or close to 8½% of GDP this year, Germany’s surplus is the largest globally, well ahead of China and Japan. It wasn’t always like that: During the 1990s, the German current account was actually in deficit and the surplus during the 1980s was on a smaller scale – the continuously rising surplus to new highs is a phenomenon of the 2000s. Even though German domestic demand – and in particular consumption – has grown far more strongly in recent years, the surplus has still widened. What is driving the increase, and is it likely to reverse anytime soon? We approach the question from two angles.

Higher income flows as stock of foreign assets increases

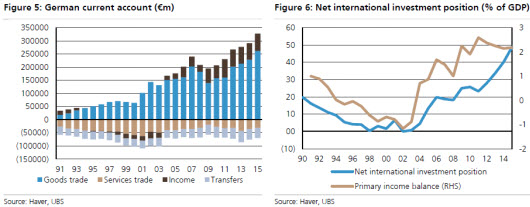

First, looking at the trade and income side, a larger trade balance is the main driving factor behind the rising surplus. In recent years, this has partly reflected lower import prices due to a smaller oil bill – but this has affected other oilimporting countries too. However, another important factor, accounting for around 20% of the rise since 2000, is rising income flows – basically the return on investment abroad. Income flows have increased from around zero in 2000 to 2% of GDP today, as the stock of German foreign investment has increased substantially, reaching close to 50% of GDP now after years of current account surpluses, and thus foreign asset accumulation.

More frugal corporates

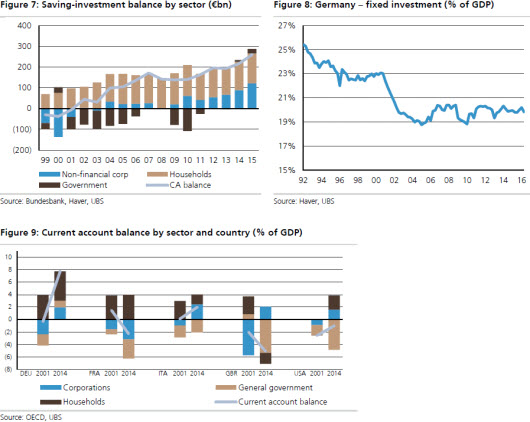

Second, the current account reflects the balance of saving and investment in an economy. A surplus denotes a situation where a country saves more than it invests, and thus channels the excess savings abroad. Germany turned from a net borrower (CA deficit) during the 1990s to a net saver (CA surplus) in the 2000s. What brought about this change? Looking across sectors, a lack of investment in Germany by corporates is the main factor, explaining more than half of the increase in the current account surplus. Instead of borrowing to invest (as during the 1990s), German corporates became net savers in the 2000s. The government budget balance also moved into surplus, contributing to the overall CA balance, but less so than the corporate sector. Finally, households increased their savings only marginally, so were not a big driver of the increase in the CA surplus.

Don’t expect much change, unless corporates start investing materially

The outlook for the CA surplus critically hinges on whether German corporates start investing more in Germany. Our UBS Evidence Lab investment survey points to some gradual cyclical acceleration in German corporates’ fixed investment plans, but likely not enough to be a game changer for the CA surplus. Structural reforms to raise the attractiveness of investments in Germany or markedly higher infrastructure spending could induce corporates to invest more. Both options do not look very likely to be implemented now, in our view. We thus expect the German surplus to remain large – and policy discussions to continue.

The large and rising German current account surplus

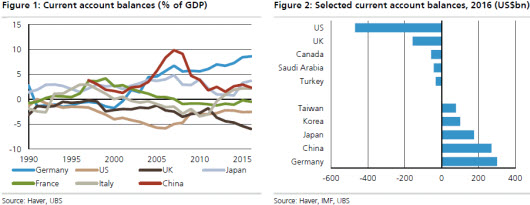

Germany is now running the largest current account surplus globally (reaching US$300 billion in 2016, according to IMF estimates), well ahead of China and Japan, and one the largest among advanced economies as a share of GDP, on track to reach 8.6% this year (Figure 1 and Figure 2).1 The size of the surplus continues to feature prominently in international and European policy discussions, and is a key reason for international organisations to demand more stimulative German fiscal policies aimed at raising domestic demand and thus import growth.

Yet, domestic demand (and in particular consumption) has grown at average annual rates of 1.5% over the past two years – more than twice its average over the period 2000-13 – and the CA surplus has continued to rise. What explains this persistence and what could lead to a smaller surplus?

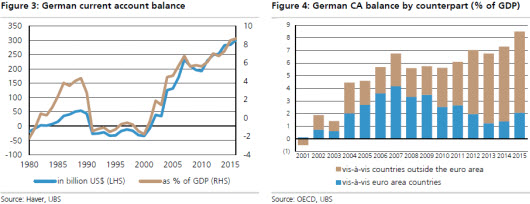

Germany did not always have a CA surplus

To start with, the German current account was not always in surplus – throughout the 1990s, Germany actually registered a deficit. CA surpluses were a common German feature during the 1980s, but on a smaller scale than now. The continuous steep increase since 2000 clearly stands out (Figure 3). While until 2009, more than half of the surplus was with other euro area countries, this share has shrunk substantially, and by 2015, more than two-thirds of the surplus was with countries outside the euro area (Figure 4).

Driving factors behind the increase

The current account balance can be interpreted from two different angles. First, it is equal to the sum of the trade balance, the income balance and current transfers. Seen from this angle, a higher trade balance is the prime reason for the rise in Germany’s surplus (Figure 5). However, higher income flows contribute roughly one-fifth to the increase. Higher income is a natural consequence of the accumulation of foreign assets (and thus of past current account surpluses) – Germany’s net international investment position has now reached 50% of GDP (Figure 6).

Another angle is that the current account describes the balance of investment and saving in an economy during one year. If an economy saves more than it invests (domestically), it channels the surplus savings abroad and this is what the current account surplus shows. Seen from this angle, Germany moved from being a deficit country during the 1990s (when it attracted more savings from abroad than it supplied to foreigners) to a massive net saver. What is behind this shift? Looking at the breakdown by sector, it appears that it is the corporate sector that changed its behaviour most: It was a net borrower during the 1990s and shifted to a net saver position in the 2000s (blue bars in Figure 7). This shift explains more than half of the rising current account balance since 2001. A persistent lack of investment in Germany (partly explained by more investment abroad rather than in Germany by German corporates) is thus the mirror image of the increase in the CA surplus.

The investment share in GDP has fallen by around 3 pct pts compared to the 1990s (Figure 8). In addition, by reducing its budget deficit, and moving to a surplus recently, the public sector also contributed to the build-up of the CA balance, by around 2.9% of GDP. Lastly, the household sector was always in surplus and that surplus rose only marginally during the 2000s – adding around 0.8% of GDP to the CA surplus increase (Figure 9).

The phenomenon of corporates moving from net borrower to net saver can also be observed in some other countries since 2000, including the UK and the US; however, in those other countries, the magnitude of the change was smaller and/or rising public deficits offset the impact on the overall current account balance.

Domestic demand strong, but more investment needed

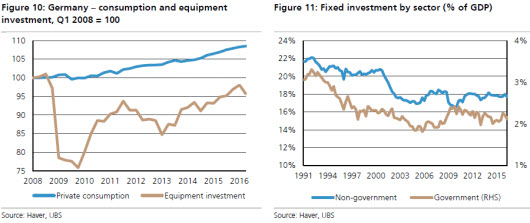

The change in corporate behaviour explains why the CA surplus has continued to increase even though domestic demand is now the key driver of growth – suggesting that the CA surplus is more of a structural rather than a cyclical phenomenon. While households are now consuming like they have rarely done since the 1990s, corporate investment is still only increasing gradually. Private consumption today stands 10% above its Q1 2008 level, while corporate equipment investment is 4% below its Q1 2008 level (Figure 10).

What are the prospects for investment picking up more forcefully? Our UBS Evidence Lab survey of investment intentions shows only a gradual increase – the net share of corporates planning to invest more over the next 12 months stood at 14% in July. This is more than in January (6%), but barely more than in Italy (10%) and less than in Spain (18%). With a bit more fiscal spending going forward and continued solid household consumption, the surplus may fall slightly, but large moves seem unlikely to us.

What could induce a more pronounced swing in the CA balance? We think a combination of more fiscal spending – notably on infrastructure investment – and structural reforms, such as deregulation of product markets and of employment contracts, could provide the basis for corporates to invest more domestically. Government investment as a share of GDP today is 1 pct pt lower than in the 1990s, mirroring the fall in business investment (Figure 11). In our view, a marked increase in public investment or substantial structural reforms to induce corporates to spend more are both not very likely. We thus expect the CA surplus to remain high – and policy discussions to continue.

Die komplette Marktanalyse als pdf-Dokument.

Ergänzend dazu:

European Economic Perspectives - Economic Outlook 2017-18

European Economic Comment - Eurozone: Steady Q3 growth and higher inflation

Diesen Beitrag teilen: