BNP Paribas: In China gibt es seit der zweiten Jahreshälfte 2020 eine Flut an regulatorischer Verschärfungen

Wie passen diese Maßnahmen in die zentrale Strategie des Landes, das seinen heimischen Sektor stärken will und einen langfristigen strategischen Wettbewerb mit den USA beginnt. Erfahren Sie es hier!

28.09.2021 | 07:42 Uhr

This is an abridged version of a paper by the same title by Chi Lo

A change in reform tactics

The economic recovery from the Covid-19 shock has given China’s leadership an opportunity to tackle structural problems by tightening regulatory oversight which favours the development of ‘hard tech’ hardware and components over ‘soft tech’ (e-commerce) expansion. This marks a shift in Beijing’s approach that had focused on consumption-driven growth.

Beijing now wants to increase high-value manufacturing to support the development of the technology and renewable energy industries in response to the changing domestic and international environment including intensified Sino-US competition.

US national security hawks have successfully hampered corporate China’s expansion through embargos and supply restrictions. Even China’s most successful companies are vulnerable.[1] Their supply chains are overly dependent on the US and its allies as China lacks the ability to produce key hardware and technology components. This vulnerability drives China’s import substitution efforts.

Soft tech, in Beijing’s eyes, has attracted too much investment and it only serves consumption and sectors that have little long-term strategic value.

Manufacturing is back

Manufacturing has regained policy favour. This has positive implications for long-term growth.

China’s domestic sector started a structural rebalancing in 2005 with lower costs and improving infrastructure driving industrialisation to poor inland provinces. This resulted in a regional division of labour, with the costly eastern region moving from manufacturing to high value-added services industries. Cheaper inland regions picked up low value-added manufacturing.

The process was reversed in 2013 when Beijing made services and consumption the drivers of economic progress. The idea was to lift the quality of growth, even if that meant a slower growth rate.

Under the current approach, industrial migration to the interior provinces is likely to resume, with high-value-added industries dominating the trend. This will revive the momentum of GDP growth and raise China’s productivity in the longer term.

The role of the private sector

Beijing attaches great importance to developing cutting-edge technologies and reducing the dependence of supply chains on external sources. It sees innovation as a way to achieve common prosperity, with digitalisation as the solution to improve economic efficiency and people’s access to modern services.

While it wants state-owned entities to do the heavy lifting on tech investment, it wants small and medium-sized companies and the private sector to drive innovative change and fund the development of hard tech.

In this context, China has announced the setting-up of a new stock exchange in Beijing offering SMEs a low-cost financing channel with simple listing procedures.[2] This is a step towards developing onshore capital markets so that they reallocate capital to the real economy.

It will also go a long way to facilitating common prosperity by redistributing wealth to the SMEs and privately owned businesses away from the state sector and conglomerates. The new exchange can be seen as a signal that private businesses would be encouraged if they help achieve the country’s strategic goals.

So the recent regulatory crackdowns are not meant to rein in the private sector. Rather, they aim at aligning the private sector interests with Beijing’s strategic targets. Those deviating from the public goals will risk being sidelined and penalised.

This approach underscores our long-held argument that economic reforms were based on the strategic use of markets under state guidance and not on using market forces to drive change.[3]

The domestic agenda

Further underscoring this argument is China’s concern over the media influencing public opinion and government policy, risking potential abuse by serving vested interests, distorting public policy and creating systemic instability. To minimise these risks, the cybersecurity regulator took board seats in some of China’s social media platforms this August.

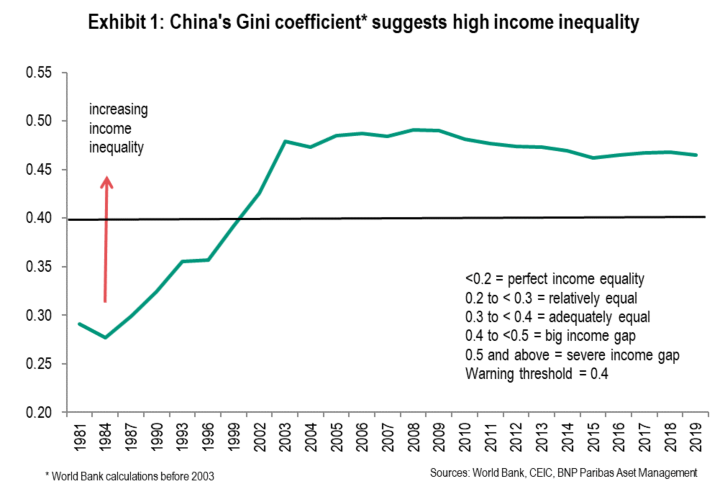

Reducing wealth inequality is now a top policy priority. President Xi sees income and social inequality as threats to long-term development. Indeed, the common prosperity policy aims at raising labour compensation as a share of GDP to help address inequality (see exhibit 1).

Faced with increased scrutiny, many large companies have announced plans to donate funds to society. However, it is unlikely that the good old days of lax supervision and regulatory forbearance will return. Regulatory execution will be tough as Beijing is determined to redistribute income and create high-value jobs by boosting innovation and technological advancement.

Implications for consumption

Such policies should lift consumption. Building a better social safety net should help reduce household savings and increase consumer confidence. Since the poor have a higher marginal propensity to consume than the rich, the positive impact on consumption of distributing income more equally should be significant.

Spending can be expected to be aimed at the mass and mid-value consumption sectors. However, distributing wealth more evenly to the SMEs and the private sector should augment aggregate income growth, allowing it to continue to drive the growth of the luxury goods sector even without policy endorsement.

Any views expressed here are those of the author as of the date of publication, are based on available information, and are subject to change without notice. Individual portfolio management teams may hold different views and may take different investment decisions for different clients. The views expressed in this podcast do not in any way constitute investment advice.

The value of investments and the income they generate may go down as well as up and it is possible that investors will not recover their initial outlay. Past performance is no guarantee for future returns.

Investing in emerging markets, or specialised or restricted sectors is likely to be subject to a higher-than-average volatility due to a high degree of concentration, greater uncertainty because less information is available, there is less liquidity or due to greater sensitivity to changes in market conditions (social, political and economic conditions).

Some emerging markets offer less security than the majority of

international developed markets. For this reason, services for portfolio

transactions, liquidation and conservation on behalf of funds invested

in emerging markets may carry greater risk.

[1] US foreign policy towards China has changed from constructive engagement, as pursued by the administrations before Donald Trump, to strategic competition. For example, see “Strategic Asia 2020: U.S. – China Competition For Global Influence”, Edited by Ashley J. Tellis, Alison Szalwinski and Michael Willis, The National Bureau of Asian Research, Seattle, Washington D.C. 2019 https://carnegieendowment.org/files/SA_20_Tellis.pdf

[2] “China’s Xi Jinping Says It Will Set Up a Stock Exchange in Beijing for SMEs”, CNBC, September 2, 2021 https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/03/xi-jinping-says-china-to-set-up-beijing-stock-exchange-for-smes.html

[3] See “Chi on China” Mega Trends of China (6): Evolution of China’s Growth Model”, 6 April 2018.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: