Schroders: The rise of young Asia - how millennials are transforming a region

We look at the huge shift of economic power towards a growing and increasingly wealthy Asian middle class, which - crucially - is both young and at ease with technology and rapid change.

14.11.2017 | 13:20 Uhr

Aren’t you sick of pieces extolling the wonderful demographics in Asia? Or how the meteoric rise of the middle classes is transforming the prospects of emerging markets? Bear with me, though, and read on. There really is a good story to be told.

The developed world has a well-known ageing population problem. However, despite the tomes written about the supposed demographic dividend accruing to emerging markets, the simple facts are that, at least in Asia, the overall demographics are no longer that favourable.

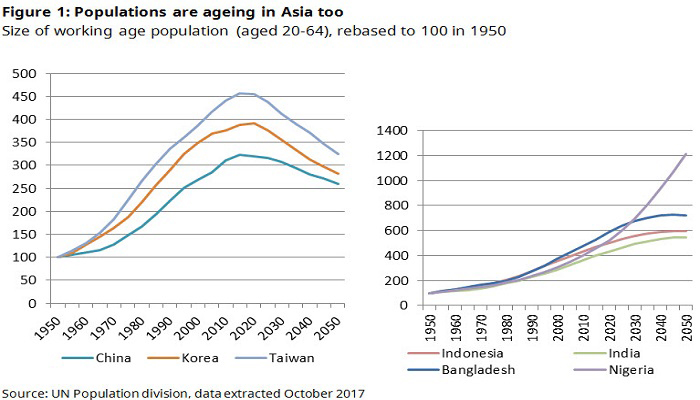

Populations are ageing, dependency ratios (the ratio of the young and very old to the working population) are rising and labour forces are projected to decline sharply across China, Korea and Taiwan (Figure 1, left-hand chart).

Demographics are more favourable in other parts of Asia – for instance, in Bangladesh, Indonesia and India – and even more so in Africa, where the working age population of Nigeria alone is forecast to increase in size by around two thirds between 2015 and 2050 (Figure 1, right-hand chart).

But many of the traditional stepping stones to national development through labour-intensive manufacturing are under threat from trends like automation, 3D printing, and “re-shoring” (moving production back to developed markets), even in tried and trusted first-rung pillars of industrialisation, such as footwear, textiles and basic IT assembly.

It looks like the “moats” – difficult-to-replicate advantages – to early development are widening. And that is before arguments over free trade, the backlash against globalisation, and the stunning undermining of those still propounding the benefits of Western liberal capitalism every time The Donald (Trump) opens his mouth, or his Twitter account.

However, despite headline demographic trends turning less favourable for Asia, a look beneath the surface suggests an altogether more positive story, providing you focus your gaze in the right places:

•Economies stand to be transformed by an emerging middle class, a well-trodden theme

•These middle-classes are predominantly young, a less well-recognised theme. This is where real economic power resides; and

•it is the spending habits of these young consumers and their openness to adopting new technology that will shape markets of the future.

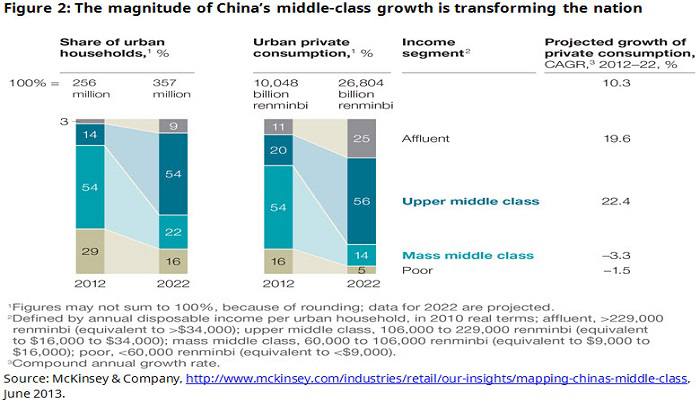

This receptiveness to new ways of doing things, largely a function of the demographic profile of Asia’s middle class, is the critical third leg to the powerful wave of disruption currently evident in Asia (see box).

These pro-youth trends are in stark contrast to the West, where the elderly have the best pensions, the highest disposable incomes and are asset-rich through the soaring value of their homes. In contrast, the young cannot get on the property ladder and are saddled with spiralling levels of university debt. Western youths may wield greater political clout (a notable example is the UK, where over 70% of under 24-year olds voting in the last General Election cast their ballots against the ruling Conservative party1, whose supporters included more than 60% of over-65-year-old voters) but they perceive themselves as second-class citizens in economic terms compared with their elders. (1. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/datablog/ng-interactive/2017/jun/20/young-voters-class-and-turnout-how-britain-voted-in-2017)

While youth in Hamburg want to throw rocks at G20 leaders, their Asian equivalents (limited though their political means of expression may be) are embracing a world of choice with enthusiasm.

The emerging middle class

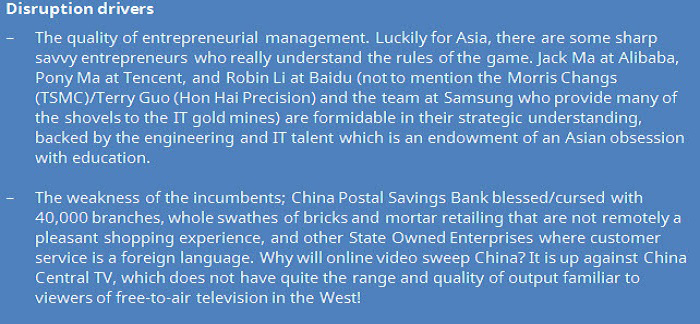

The rise of the middle class in emerging markets is well documented. Taking China (which inevitably dominates the global numbers) as an example, the number of affluent and upper middle-class households is projected to increase from 17% of the total in 2012 to 63% by 2022, a meteoric rise.

By 2022, over 80% of private consumption expenditure is forecast to come from these two economic groups (Figure 2).

The young are the economic winners

Less well-recognised is the extent to which this is a relatively young cohort.

The Deloitte Millennial Survey 2017 found that emerging millennials were more confident about their economic prospects and expected to be materially and emotionally better off than their parents, in stark contrast to those in mature markets.

Millennial wealth is projected to more than double between 2015 and 2020 to somewhere between $19 trillion and $24 trillion(2). To put this into perspective, US GDP is projected to be only $22 trillion at that date and the eurozone economy $13 trillion. Chinese millennials are clearly a force to be reckoned with. (2 “Millennials and wealth management, trends and challenges of new clientele”, Inside, issue 9, Deloitte, June 2015)

While ageing and fabulously wealthy Asian tycoons still feature largely in the popular imagination, the real economic influence in Asia is middle class and, crucially, young.

Dubbed the G2 generation by McKinsey, these are “typically…born after the mid-1980s and raised in a period of relative abundance.” It continues (our emphasis throughout)(3):

(3 Source: McKinsey & Company, http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/mapping-chinas-middle-class, June 2013.)

“These G2 consumers today are typically teenagers and people in their early 20s, born after the mid-1980s and raised in a period of relative abundance. Their parents, who lived through years of shortage, focused primarily on building economic security. But many G2 consumers were born after Deng Xiaoping’s visit to the southern region—the beginning of a new era of economic reform and of China’s opening up to the world. They are confident, independent minded, and determined to display that independence through their consumption...

“McKinsey research has shown that this generation of Chinese consumers is the most Westernized to date. Prone to regard expensive products as intrinsically better than less expensive ones, they are happy to try new things, such as personal digital gadgetry…

“Teenage members of this cohort already have a big influence on decisions about family purchases, according to our research.”

McKinsey estimates that, in 2012, this group comprised 200 million consumers, accounting for 15% of urban consumption, a figure which it expects to rise to 35% by 2022.

The same phenomenon is evident in India. Recent survey data show that millennials’ gross income is significantly higher on average than that of the older generation (a trend also evident in China and all the Emerging ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) markets), while 57% of all working millennials in India are the chief wage earners in their families (Figure 3).

In a simplistic sense we are already seeing the more obvious effects of this rising wealth in trading up by consumers. Not just the well-worn theme of the Asian love affair with luxury brands. (Indeed, there are signs that the market for Prada handbags and French Premier Cru is now suffering from overkill.)

More sustainably, the Chinese are trading up in areas such as home appliances, fitted furniture, kitchen equipment and tourism. Importantly to us as investors, many of the beneficiaries of this trend are domestic brands accessible via A-shares, traded in the local Chinese equity market.

More interestingly, this is a generation which feels completely at home with technology and wants to embrace it. The level of engagement is staggering. It’s not just the numbers – 963 million monthly active users (MAU) on the WeChat/Weixin social media service or 340 million on the Sina Weibo microblogging service – but the breadth and depth of its level of engagement.

WeChat (the core service operated by Tencent) has been installed by 97% of all Android users in China, and 86% of WeChat’s reported MAU are active daily, compared with 66% for Facebook3. Over half of users are on the service for at least 90 minutes a day, and over a third for a staggering four hours or more.

Unsurprisingly, the penetration by online retailing is surging and, again, it is the age profile of the customer base which is immediately striking (Figure 4).

It is evident in other areas too. Online travel bookings are now 40% of the total in China, up from just over 15% five years ago(5). Chinese consumers’ desire to act on the hoof is further evident in that half the online total is executed from a mobile device. Already the gross bookings revenue for CTrip, China’s leading online travel agent, is equal to more than half that of either Expedia or Priceline. (5 Phocuswright’s Asia Pacific Online Travel Overview Eighth Edition, July 2015)

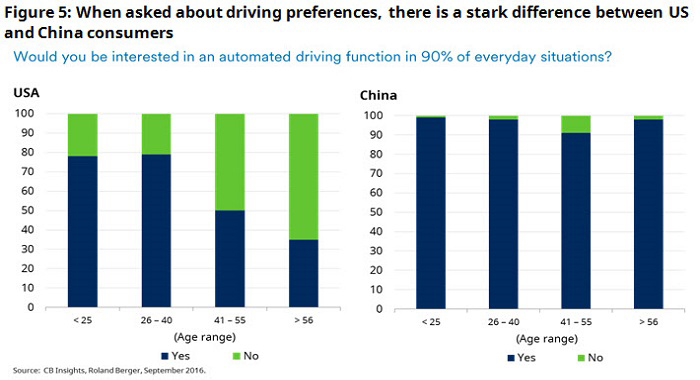

Openness to change even extends to automated driving. Personally, I would rather drive myself, even if there is a risk I might run into the back of a truck, but this is clearly not a preference shared by Chinese travellers. Strikingly, it seems that every age group is ready to embrace automated driving (Figure 5).

It is rare to find even a mention of the invasion of privacy that much of this implies as stacks of data are collected and used across the digital complex.

Perhaps there is tacit acceptance that in many Asian societies, there is nothing that can be hidden. Inevitably, there will be flurries of opposition from vested interests (for example, from the big state-owned banks over the expansion of fintech and electronic payments), but there is little sign of anything akin to an Asian version of Margrethe Vestager, the EU commissioner for competition who has tackled the practices of Apple and Google head-on.

Clearly, it is highly convenient for governments to centralise so much data on their citizens. Nonetheless, we have heard few complaints about the Chinese government handing over 80 exabytes of medical data to researchers in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). (For the uninitiated, one exabyte is equivalent to all the words spoken by human beings – ever.)

Inevitably the here and now is dominated by China. Once the political will was there, the rest followed given the advantages of scale, economic heft and homogeneity that China uniquely possesses. However, do not underestimate the speed of adoption in other Asian markets, where the basic conditions in terms of average wealth, youthful open-minded populations and weak incumbency co-exist.

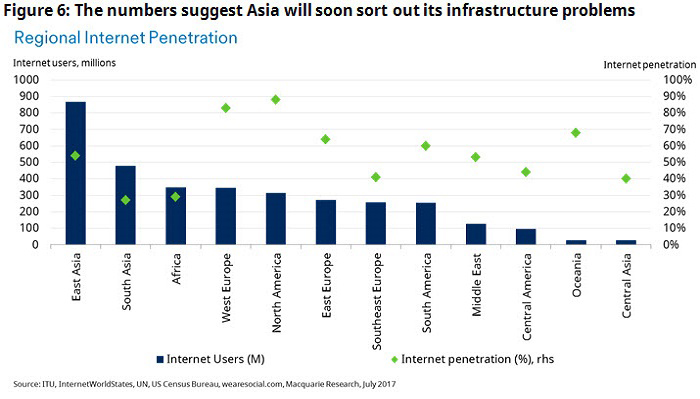

This is clear in Asia’s adoption of the internet. Despite the many infrastructure challenges faced by the web, they will be overcome. The situation where East Asia has almost 900 million internet users but only 55% penetration, or South Asia has almost 500 million with under 30% penetration is only going to resolve itself one way (Figure 6).

Indeed, in Indonesia, a classic “difficult” market, it is already happening. The country boasts the third-largest Facebook user base in the world, with 40 million transactions a month going through the GO-JEK app, a transport service akin to Uber, while Alibaba and Tencent are pouring in the money.

Investment conclusions

So as investors, what are the lessons? Don’t write off Asia based on the simple extrapolation of demographic trends. There is a massive shift of wealth going on and the beneficiaries are young, middle class, technologically savvy and open to change. In these circumstances, valuations still matter, while there will be many losers as well as winners from the rapid changes we are witnessing. Unsophisticated investment strategies are unlikely to be able to differentiate between the two.

However, active investment should continue to provide rewards as Asia becomes increasingly a leader rather than a follower in the application of genuine innovation.

Die hierin geäußerten Ansichten und Meinungen stellen nicht notwendigerweise die in anderen Mitteilungen, Strategien oder Fonds von Schroders oder anderen Marktteilnehmern ausgedrückten oder aufgeführten Ansichten dar. Der Beitrag wurde am 01.11.17 auch auf schroders.com veröffentlicht.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: