NN IP: The protectionist shark shows more of its teeth

The trade war risk continues to threaten global growth recovery. In emerging markets, we make a modest adjustment to growth prospects.

19.07.2018 | 13:49 Uhr

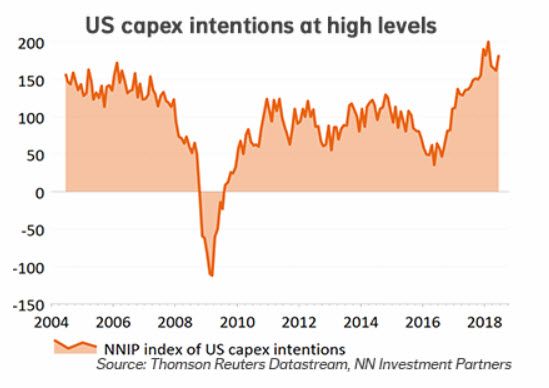

As we argued last week, global growth is recovering from its Q1 soft patch on the back of a pronounced rebound in consumer spending and some better high-frequency capex indicators. With respect to the latter, the combination of solid profit growth and high levels of business confidence and capex intentions point to decent growth rates in the foreseeable future. By far the biggest threat to this happy state of affairs is, of course, the risk of a full-blown trade war. Last week, the US published a list of USD 200 bn worth of Chinese imports to which it intends to apply a 10% tariff. Clearly, President Trump wants to take his shock and awe approach to trade to the next level. China was “shocked” and stated that it “has no choice but to take necessary countermeasures”. However, China did not repeat its previous threats that the response would be on “the same scale and intensity” and that it would respond with “both quantitative and qualitative measures”. To interpret the absence of these key phrases, it is instructive to bear in mind that escalation in a trade war is a means to learn about the other players’ willingness to retaliate. Therefore, one reason could be that China may feel it is in its own long-term interest not to retaliate to the same extent. This is a difficult balancing act because if the other player in this trade game does not bark or bite hard enough, President Trump may see this as an invitation to increase the stakes in the game.

Still, it pays to think about the economic consequences of retaliation. The one period in history where retaliation happened on a large scale was in the early 1930s when overall global demand was severely depressed due to restrictive fiscal and monetary policies, and countries tried to steal demand from each other. That incentive seems much less relevant today. Another reason for imposing tariffs could be a desire to improve your terms of trade by depressing import prices on the world market and cashing in on a nice source of government revenue. However, neither China nor Europe seem interested in this. On the other side of the equation, too much retaliation by Europe and China could reduce their own gains from trade, which they could perhaps preserve to a larger extent if they decide to form a coalition against Trump. An added advantage of this would be that in doing so, they increase the probability that the rules-based international trade order will be preserved. The growth model for both China and Europe is more dependent on exports and neither directly benefit from a near-term and large fiscal boost to demand. Nevertheless, as argued before, all this must be weighed against the risk that giving in to Trump’s demand may lead him to make bigger demands in the future. In the case of China, a strong aversion to an appearance of losing face on the global political stage also plays a big role.

It is important to bear in mind that the USD 200 bn announcement is only an intention and it will take a few months before it becomes reality. However, in the meantime this announcement could of course have a detrimental effect on business confidence and financial conditions. A lot will depend on the further reaction of China, which cannot put a tariff on an additional 200 bn of US imports because the US exports less than that. One option is to apply a higher tariff but there is a limit to that because beyond a certain point, trade in a particular good will cease entirely. A more promising alternative would be qualitative measures in the form of additional barriers for US companies operating in China. A third option would be large-scale RMB depreciation to offset the tariff effect. But given that a large-scale depreciation could unleash further depreciation expectations and trigger persistent capital outflows, this instrument will not be used lightly. The best-case scenario would be a resumption of trade talks but after this big move by Trump, that would probably take a phone call at the highest level.

A closer look at the US and Europe

As previously contended, the US economy is best positioned to weather the short-term impact of trade uncertainty because it benefits from a fiscal boost, which will raise growth by 0.5-1pp both this year and next. However, under current legislation the hangover will come in 2020 when fiscal policy will act as a drag on growth. This drag may come at a time when US investment spending feels a drag from the expiration of tax incentives, while global capex may slow down as the current constellation of fundamental drivers (profit growth, confidence, cost of capital, investment to GDP ratio etc.) becomes less favourable. All this is happening in an economy with an unemployment rate of around 4%, which is set to fall further as long as growth momentum remains well above 2%. How much further the unemployment rate will fall is a difficult question to answer because it will depend on the supply side response. The latest employment report, in which participation rose again after a string of three consecutive declines, kept hopes alive that an increase in labour supply growth triggered by a hot labour market may slow the decline of the unemployment rate. Indeed, the prime age male participation rate is still below the 2006-07 average but part of that may be structural due to higher rates of disability on the back of rising levels of opioid use. In addition to that, a further rise in underlying productivity growth may also slow the pace of the unemployment rate decline while at the same time triggering a decline in the NAIRU. The reason for the latter is that a higher rate of productivity growth will make posting a vacancy more profitable. Unless workers manage to seize all of these marginal gains, the ratio of vacancies to unemployed will rise. This will make it easier for the latter to find jobs, especially in an environment where workers are better trained.

While it makes sense to believe that productivity growth will rise on the back of increased investment and a more dynamic economy (where resources can more easily move towards productive uses) an escalation of the trade conflicts will undoubtedly act as a drag on productivity growth. Adding it all up, it is clear that the Fed may well find itself in a pretty challenging environment some 18 months down the road. In the near term, unemployment is likely to continue to decline while inflation momentum has improved relative to last year. With respect to the latter, there is still no sign of an acceleration in wage growth. And after years of missing the inflation target on the downside, the Fed will feel quite relaxed about a moderate overshoot for a while. Still, it is clear that from a risk management perspective the Fed is focused on mitigating overheating risks, which will keep it in a gradual hiking mode at least until the real policy rate reaches neutral territory. With respect to the latter, uncertainty once again reigns supreme as various point estimates for r-star used by the Fed range from 0.1% to 1.8%. What’s more, going forward r-star is likely to be influenced by the cross-currents mentioned previously. The fiscal boost and high levels of business confidence are likely to push r-star higher and the Fed will feel compelled to follow this to prevent monetary policy from loosening. However, there is a risk that in 2020 the fiscal drag, an investment slowdown and possibly a trade drag on productivity growth will trigger a decrease in r-star. If the Fed does not react, there will be an endogenous tightening of policy which will come on top of the other growth drags. In this scenario, the Fed will probably act with a lag because it takes time to discern a persistent trend in the noisy data flow.

A scenario like this is already on the minds of some market participants but it would be wrong to overly focus on it because there are simply too many moving parts, some of which are working in opposite directions and all of which are surrounded by considerable uncertainty. In the more immediate future, the US economy benefits from the combination of strong employment growth and a continued very healthy level of investment intentions (see graph). These should keep the feedback loop between private sector income and spending growth spinning quite nicely, also because fiscal policy is adding to it.

The Eurozone economy is more sensitive to trade risks because exports make up a larger share of GDP than in the US, while the region does not benefit from an offsetting positive fiscal shock. In addition, the Fed could in principle react to any negative effect on final demand stemming from trade risks even though the hurdle for doing so would be quite high (that said, there is little the Fed can do about negative supply side effects). However, when it comes to further easing options, the ECB is standing with its back very close to the wall. The heightened trade risks come immediately after a period marked by increased doubts about the resilience of the region’s above-potential growth momentum. A stellar performance in Q4’17 was followed by a substantial slowdown, especially in data related to the external and industrial production sectors. Since then, the search party has been out to find the most likely culprits, because finding them gives us more information on the question of whether this is a soft patch or a more persistent slowdown. Topping the list of suspects one always finds shocks to financial conditions and oil prices. Despite the turmoil on financial markets, lending rates for households and business remained on a moderate downward trend and credit standards were still being eased in Q1 and Q2. As for oil prices, one can expect them to act as a temporary drag on consumer spending growth but strong employment growth, high levels of consumer confidence and some incipient signs of wage growth should keep households in a spending mood nonetheless.

Upon closer inspection, the weakness was largely trade-related, which means that it can be traced back to the slowdown in global industrial production momentum we observed at the start of the year. This slowdown owed partly to one-off factors in Q1 (weather distortions, strikes etc.) and partly to a drag from elevated inventory levels. Nevertheless, it appears that the Eurozone was high beta on this slowdown, which is a bit harder to explain. Euro strength in 2017 may be part of the reason, as this always operates with a lag. On top of that there may have been other Eurozone-specific factors. Some point to growing evidence of supply-side constraints in some of the survey data. While these may play a role in some (sub)sectors, we doubt they are already very relevant for the economy as a whole. After all, if they were one would expect to see a combination of an investment boom in an effort to raise productivity, accelerating wage and price inflation and a reduction in net exports as the rest of the world satisfies a higher fraction of EMU domestic demand. None of these are visible in the data yet. Even so, investment intentions in the region remain at the highest level since the bounce back from the steep capex decline of 2009. Provided trade worries do not throw a spanner in the works, these intentions could well become a reality given the healthy level of profit growth and the fact that investment to GDP is still well below trend.

Emerging markets: modest adjustment in growth prospects

In the last few weeks, market pressure on EM has softened somewhat. This has been most clearly visible in EMD, where local and hard currency yields have declined, and in currency markets, where we have seen the first meaningful appreciation since February. It is still early days, but it is encouraging to see EM recovering despite the dangerous macro-economic dynamics in Turkey and the ongoing trade noise created by the Trump administration.

One of the main issues EM investors are currently facing is the potential impact on growth from the market turmoil of the past months. It is no surprise that we have seen a clear tightening of financial conditions in EM since April. Our own EM financial conditions indicator, which we have been using since 2012, has entered negative territory for the fourth time. The first time was in Q2 2013, around US tapering, the second time in Q3 2015, around the August renminbi depreciation, and the third time was in Q4 2016, following the Trump election win. The current tightening of financial conditions is sharper than in 2015 and 2016, but less pronounced than in 2013. One of the main differences with 2013 is that investor positioning in EM has been less of a problem, which has prevented a dramatic capital outflow. Q2 net outflows from EM amounted to USD 93 billion, which compares to an inflow of USD 85 billion in Q1. In 2015, quarterly outflows reached USD 300 billion, to put the recent numbers in perspective.

So far, the impact of the tightening of financial conditions on EM growth has been manageable. Our EM growth momentum indicator has moved into negative territory but remains at much better levels than in 2013 and 2015. The main explanation lies in China, where growth is slowing in an orderly way, and in the overall EM imbalances, which are considerably lower now compared with 2013. We expect a large growth adjustment only in the few countries where external and fiscal imbalances remain large and where policymakers are not doing their homework. Turkey remains the best example. For the broad EM universe, we expect a growth slowdown from 5.5% in Q1 2018 to 4.9% on average in 2019. The earlier projected softening of Chinese growth explains half of this decline.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: