BNP Paribas: Decoupling from China? Not really – Just a shift in Asian supply-chains

Since the Sino-US trade war in 2018, some large developed countries have been pushing to reshore their global production, in effect seeking to ‘decouple from China’.

03.09.2021 | 07:10 Uhr

Chatter about such a trend has raised concerns that Asian supply chains, which underpin China’s role in global trade, could break apart. This in turn would bring into question the rationale for investing in Asia, including China.

In fact, Asia’s supply chains have so far simply shifted rather than broken down or contracted. Indeed, contrary to conventional wisdom, Asian supply links have integrated further with China in a way that differs from the general market understanding of these relationships.

Amid the fall-out from Sino-US trade war, restrictions on technology transfers – among other disruptions to trade – are creating the greatest uncertainty for Asia, as a third of the region’s exports are electronic and tech products.

In addition, the Covid-19 crisis has aggravated concerns about Asia’s manufacturing outlook as it has disrupted global supply chains and created shortages of everything from automotive parts to semiconductors.

Asian supply chains are not breaking, just shifting

Some large developed market companies may have cut their sourcing and/or manufacturing operations in Asia and shifted them elsewhere. There is however no meaningful trend of decoupling from either the region or China.

Firstly, despite the trade war and the pandemic, which severely depressed demand, Sino-US bilateral trade has continued to rise (see Exhibit 1), defying expectations. This is partly because US shipments to China have picked up, even though Chinese purchases have fallen short of the January 2020 US/China Phase One agreement. Secondly, rather than reducing their reliance on Asian supply chains, US importers have increased imports from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

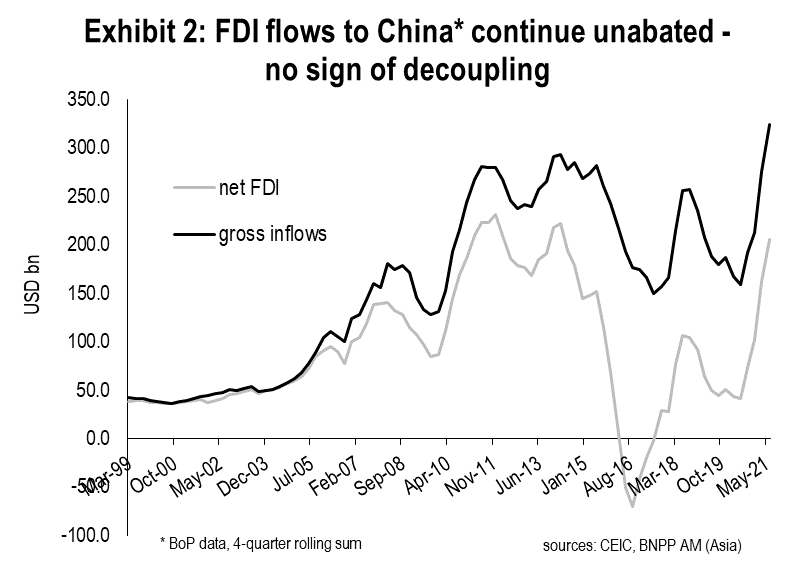

Hence, there is a shift rather than a shrinkage or breaking of Asia’s supply chains. Take the tech sector, the epicentre of Sino-US competition. While policy risk has prompted companies to re-evaluate their production locations, there has been no great exodus from China. On the contrary, foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into China have continued to rise, both in gross and net terms

No decoupling in sight

Buying more from ASEAN does not mean buying less and/or decoupling from China. Rather, it often indicates implementation of the so-called ‘China-Plus-One’ risk diversification strategy, under which companies keep producing in China for their domestic market while moving some capacity elsewhere, notably to ASEAN. This partial relocation is a means of managing the supply chain disruption due to economic, political and, most recently, Covid-19 considerations.

The rising trend in FDI flows to ASEAN indicates an expansion of China-Plus-One strategies. This confirmation of China’s central role in global supply chains underscores our long-held ‘Invest in China for China’ view since the US shifted its China policy from constructive engagement to strategic competition in 2016.

Crucially, a large share of the FDI flows to ASEAN come from China, which now accounts for 40% of the total, compared to only 10% a few years ago. This only strengthens the supply chain integration between ASEAN and China, which obviously runs counter to the decoupling notion, but in a different way.

Components used to be shipped from ASEAN to China, which then manufactured them into finished products to be sold to the world markets. That made China ‘the world’s factory’. Now the process seems to be reversing, with China supplying ASEAN products that power the region’s exports to the world.

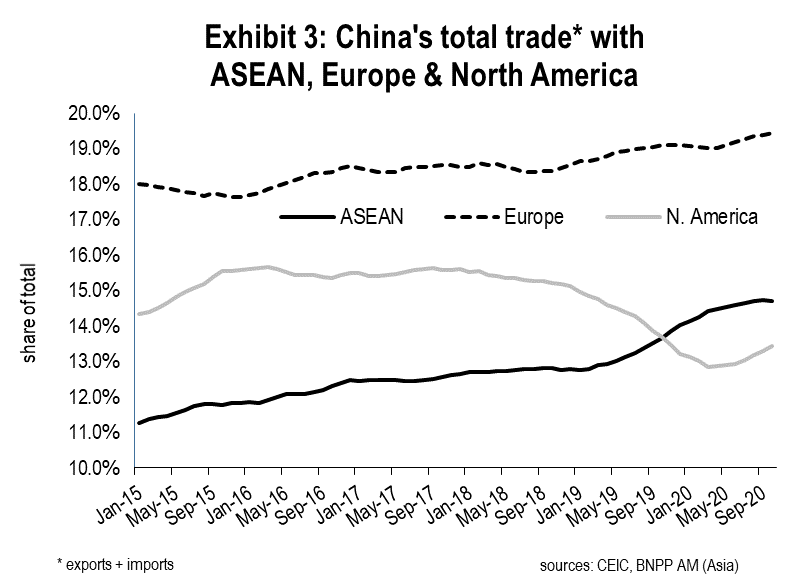

This shift in the supply-chain integration process has expanded ‘the world’s factory’ to include both China and Asia. Indeed, Sino-ASEAN trade exceeds the size of Sino-US trade (Exhibit 3), reflecting not only the huge potential of economic linkage between the two parties but also their cooperation throughout the pandemic, despite shrinking global demand and increasing protectionism.

Longer-term implications

Asia’s supply chain shift also reflects China’s ‘dual circulation’ policy of using its internal growth impetus to drive domestic and regional growth. Arguably, this forms a basis for long-term investment in emerging market Asia and China. From a regional perspective, Asia’s supply chains have proven highly resilient in staving off disruptions to the global trade system.

From the macroeconomic perspective, we believe this development will likely lead to the rise of regionalism, with strong intra-regional economic linkages against a de-globalisation backdrop. With inflation concerns now rising in the developed world and companies facing rising input price pressures, the cost advantages of sourcing from Asia, whose supply chains have integrated further with China, are gaining in critical importance.

In the post Covid-19 world, domestic demand growth, import substitution and technological self-sufficiency look set to drive investment decisions and opportunities in China. For the regional economies, all other things being equal, those sectors and companies that cater for Chinese demand and those that are capitalising upon the supply-chain shift to cater for world demand should be favoured in terms of investment considerations.

In a nutshell, there are subtle shifts underway that should make Asia – and ASEAN in particular – an emerging production hub for world markets. There is little evidence of global or regional decoupling from China, which remains the key player in global supply chains; one can run, but one cannot hide from the Middle Kingdom.

Any views expressed here are those of the author as of the date of publication, are based on available information, and are subject to change without notice. Individual portfolio management teams may hold different views and may take different investment decisions for different clients. The views expressed in this podcast do not in any way constitute investment advice.

The value of investments and the income they generate may go down as well as up and it is possible that investors will not recover their initial outlay. Past performance is no guarantee for future returns.

Investing in emerging markets, or specialised or restricted sectors is likely to be subject to a higher-than-average volatility due to a high degree of concentration, greater uncertainty because less information is available, there is less liquidity or due to greater sensitivity to changes in market conditions (social, political and economic conditions).

Some emerging markets offer less security than the majority of international developed markets. For this reason, services for portfolio transactions, liquidation and conservation on behalf of funds invested in emerging markets may carry greater risk.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: