Schroders: How frightening is quantitative tightening?

We examine some of the potential consequences for markets when the Fed removes the punchbowl of QE. Will it be as boring a process as Janet Yellen hopes? A high level of uncertainty surrounds the Federal Reserve’s reversal of quantitative easing, otherwise known as balance sheet normalisation or quantitative tightening.

06.09.2017 | 13:57 Uhr

In a similar way, uncertainty surrounded QE’s introduction in 2008. While investors quickly grasped that it was bullish for asset prices (and have seldom looked back since), they also thought it would be highly inflationary for the real economy. This has not been the case.

Understandably, Fed officials are playing down the significance of shrinking its balance sheet. Only last week, Fed President Williams remarked “we’re trying to make it boring”. In June, Janet Yellen said she hoped the process would be akin to watching paint dry. Here, we’ll attempt to evaluate whether that is the most likely scenario.

Extreme monetary loosening

“The US government has a technology called a printing press (or today its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many US dollars as it wishes at no cost, ” Ben Bernanke, November 2002

Between 2009 and 2014, the US Fe

deral Reserve created $3.5 trillion during three phases of QE. It used that money to buy $3.5 trillion dollars worth of financial assets – principally government bonds and mortgage backed securities issued by the government-sponsored entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Now, a quick exercise to provide context to that number. Let’s say a shopper is tasked with spending $20 per second and has to do so 24 hours per day until penniless. For example, a shopper beginning with $100 could shop for a mere five seconds; a shopper beginning with $1,000 could shop for 50 seconds, and so on. For some, this might sound like nirvana (much like the above quote). But imagine having to do it for 578 days straight! Even worse, imagine then finding out that having only spent $1 billion, you’re not even 1% done… not even 0.1% done in fact!

If that doesn’t make you pause for thought, understand that in order for you to spend what the Fed has printed and spent through its quantitative easing programme at a rate of $20 per second, it would take you the grand total of 5,547 years, give or take. So if you started in around the year 3530 BC, you’d be just about done. Phew!

The point is that $3.5 trillion is a pretty large amount of money. One which you would expect if spent over a six-year period would distort the price of anything, bond markets included.

Before looking at how the Fed plans to unwind its balance sheet, let’s reflect on what QE has helped facilitate for the real economy, at least in the short-term. Note that throughout the following paragraphs we’ll be using the following terms interchangeably: bond yields, market interest rates and cost of credit – they’re all essentially one and the same:

First things first; the initial rounds of QE injected money into the economy at a time when the banking sector was deleveraging. An important lesson from the Great Depression was to not allow broad money growth to turn negative. QE helped to avoid that. It has subsequently been used as a tool to realise other objectives…

By lowering market interest rates, QE has permitted the government to run budget deficits more cheaply than would otherwise have been the case. Indeed, as any profits earned by the Fed on its bond holdings are remitted back to the Treasury department, these deficits have effectively been part-funded free of interest. In case that sounds inconsequential, last year alone the Fed returned $92 billion of ‘profit’ to the government, reducing the budget deficit by 14%. Between 2009 and 2016, the total amount remitted has been $676 billion. To the extent that this has enabled the government to run larger deficits than would otherwise have been the case, it has incrementally helped stimulate the economy.

Lowering market interest rates has also stimulated the economy by making private sector credit more affordable. For the household sector, this has helped sustain consumption growth in spite of stagnating wages. Indirectly, it has also created a positive wealth effect for consumers by pushing up the prices of stock, bonds and real estate. Household net worth currently stands at an all-time high of approximately $90 trillion – some 60% higher than its low of 2009.

Judging the consequences for the economy of reducing the cost of credit to the corporate sector is more complicated. In the short term it can be argued that it has been beneficial for both profits and P/E multiples, therefore contributing to the positive wealth effect described above. On the other hand it can also be argued that it has encouraged financial engineering over capital investment; reducing future productivity growth, as well as impeding the process of creative destruction by allowing weak companies to stay alive - leading to a decline in the longer-term structural growth rate of the economy.A critical point to note, however, is that governments, households and the corporate sector are all more leveraged today than they were pre-crisis, making the system potentially very sensitive to higher interest rates and thus more fragile.

For now though, we think most would argue that the benefits of QE have outweighed the potential costs and risks. It remains to be seen whether this will remain the case as the programme is unwound.

Extreme monetary tightening?

“I have absolutely no doubt that when the time comes to reduce the size of the balance sheet we’ll find that a whole lot easier than we did when expanding it,” Sir Mervyn King, February 2012

At present, when the bonds owned by the Fed mature, it simply reinvests the proceeds into new bonds, thus keeping the size of its balance sheet stable while having very little impact on the market. However, when quantitative tightening begins, the Fed will start tapering these reinvestments, allowing its balance sheet to gradually shrink.

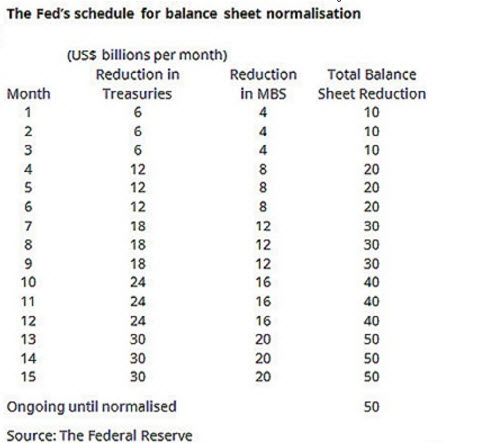

Over time, the plan is to reinvest less and less - as per the schedule reproduced in the table at the foot of the article - until such a time as it considers its balance sheet ‘normalised’.

Incidentally, the Fed has not communicated what it considers its normalised balance sheet size to be. We’re not surprised by the desire to be vague here, as a lot will depend on how the economy and financial markets behave. What we assume though is that the Fed will not seek to unwind the full $3.5 trillion, as the balance sheet has always grown naturally over time, reflecting a steady increase of currency floating around the economy.

It is currently expected that QT will begin in October, at the start of the US government’s 2018 fiscal year. Richard Koo at Nomura estimates that, assuming currency in circulation continues to expand in line with its recent trend, the programme will continue until June 2021 (all being well), contracting the balance sheet by approximately $2 trillion.

So, the obvious question at this point is: if QE pushed interest rates lower and asset prices higher, why would the opposite not unfold under QT?...and there is the $3.5 trillion question!

We expect the Fed will have three basic objectives when it comes to unwinding its balance sheet:

Don’t crash the bond market

Don’t crash the stockmarket

Don’t crash the economy

If the risk of any of these becomes uncomfortably high (most likely brought about by bond yields jumping), the Fed has already hinted that it could either resume reinvestments to stabilise its balance sheet, cut short-term interest rates, or in extremis re-expand the balance sheet through further asset purchases (QE4).

For those of a bullish disposition who interpret that as an effective ‘put’ and a green light to buy bonds at microscopic real yields and/or equities at record high prices, what follows is a closer look at the challenges of unwinding the programme.

Objective no.1: Don’t crash the bond market

As mentioned above, keeping bond yields from moving sharply higher is critical to the success of QT.

In theory, through passively unwinding its balance sheet by just allowing the bonds it owns to mature, the Fed circumnavigates the fear of what might happen to yields if it was to ever try and sell such a large amount of bonds directly.

In practice however, there is next to no difference. The Treasury, for instance, doesn’t actually have the money available to repay the Fed for its maturing bonds. As such, it will need to issue new debt in the form of ‘refunding bonds’ to the private sector in order to repay the Fed. This will have exactly the same economic effect as if the Fed had sold the bonds directly.

The proceeds from these refunding bonds will then be transferred from the treasury to the Fed, who will retire it, removing it permanently from the bond market and simultaneously shrinking its balance sheet.

Referring again to the Fed’s schedule in the appendix, you will see that the numbers we are talking about here are hardly trivial. Assuming the programme gets underway in October, the Fed stands to retire $300bn in FY2018 and $600bn in FY2019. For reference, $600 billion is roughly equivalent to the federal budget deficit last year. According to the US Office of Management & Budget, the deficit is projected to average $519 billion per year between 2017 and 2021. This is before making any allowance for President Trump’s plans for both tax cuts and increased spending, so the numbers could be significantly higher.

Collectively, this equates to a massive amount of new supply – $2 trillion or higher in the next two years. This is the equivalent of literally doubling the size of the budget deficit out to 2021. While we have little doubt that these bonds will be bought, the question is at what price, or more specifically, what yield? The levels of compensation bond investors currently receive across the risk spectrum range from negligible in real terms (government bonds) to among the lowest in history (high yield). To an extent, this is a consequence of the artificial suppression of yields elicited by central banks through QE.

With a significant increase in supply hitting the market in coming years and the largest uneconomic buyer exiting stage left, pressure should build for yields to move higher.

There is an additional risk facing the market for corporate bonds. While their yields would most likely move higher in sympathy with those of government debt, corporate securities are also vulnerable to a re-widening of credit spreads that have been crushed as a result of the global reach for yield. That corporate bonds have been sold to many low-risk investors seeking to offset the negative real returns from cash should be of great concern here.

Objective no.2: Don’t crash the stockmarket

The equivalent outcome for the equity market – effectively an increase in risk premia – would manifest itself in a falling P/E multiple. Generally speaking, the US stockmarket today is richly priced on pretty much every meaningful measure one cares to analyse. In practice this means that:

Future returns for the balance of this cycle will likely be dismal, particularly on a risk-adjusted basis - regrettably just at the point where past returns appear most impressive, inspiring a wave of passive investment

Stocks are rather vulnerable to a negative shift in fundamentals and/or a bearish swing in investor sentiment

Although this has been the case for some time now, it has been overcome by the liquidity support central bankers have provided by remaining spectacularly dovish nine years into this recovery. Investors have been conditioned to buy every dip. We would merely ask for how long that will remain the correct response going forward as liquidity is withdrawn. An additional consequence of QE has been the collapse in volatility to historically very depressed levels. We think it’s complacent to expect it to remain so low.

Objective no.3: Don’t crash the economy

Boiling it down for the economy, the crucial question for the US (and globally) is what happens to the cost of credit. As mentioned above, governments, households and the corporate sector are all more leveraged today that they were when the world began falling to bits a decade ago as a result of too much debt.

Gary Cohn, who is currently President Trump’s chief economic adviser and a frontrunner to replace Janet Yellen as chair of the Fed next year, recently said “If we woke up tomorrow and every central bank in the world raised their interest rates by 300 basis points, the world would be a better place.” In many ways, we think that’s right. Sadly, in practice there’s just too much debt in the world to allow it to happen.

We’ve written previously about how the economy has changed from decades past, but essentially since interest rates peaked and began falling in the early 80s, credit has replaced savings as the driver of economic growth. When credit growth was strong, economic growth was strong. When credit growth was weak, as has been the case this cycle, economic growth has been weak.

All else being equal, we think it’s reasonable to assume that if interest rates move higher as a result of QT, private sector credit growth, which is already slowing, will slow further. This may be compounded by a negative wealth effect if asset prices move lower too.

All of which places even more emphasis on resolving the absolute disarray in Washington. Suffice to say that the combination of a gridlocked government and a sluggish consumer is not great for the overall economy.

For all of these vulnerabilities, it is easy to see why many believe the Fed won’t make much progress with unwinding QE. The economy and the markets simply won’t permit it.

Concluding thoughts

We began this note by highlighting that there was a lot of uncertainty surrounding QT. What we have tried to do is draw attention to some of the realities of what the Fed is trying to do.

Unwinding a significant proportion of its gigantic balance sheet without disturbing the economy or markets, quite frankly, looks challenging. It’s never had to be done before. Moreover, there are a number of questions that remain unanswered. Here are six:

What is the Fed’s tolerance for rising bond yields?

How will they respond if the S&P falls 20%?

How tapped out is the consumer, and what is their sensitivity to higher interest rates?

If credit spreads rise, will companies continue to issue debt to buy back shares?

If all goes well, how long will it be before other central banks begin reversing their unconventional policies?

What policies will President Trump put in place? Will they be inflationary? Will they push up interest rates?

Now, does all of this uncertainty mean you shouldn’t invest? No. Does it suggest you ought to be investing conservatively? In our view, yes. Does it mean that you should ensure your portfolio and risk tolerance are properly aligned? Absolutely!

According to FactSet, over the past five years, trailing earnings per share for the S&P 500 have risen by 12% in total – roughly in line with the rate of inflation. Over the same five years, the S&P index has risen by about 72%. Put simply, quantitative easing has inflated asset prices. In hindsight, you’d have hoped its unwind would be taking place at a time when the economic cycle was less mature than it appears today. But we are where we are.

To the extent that watching paint dry really is rather boring, we’re going to have to disagree with Janet Yellen on this one. We expect the next few years to be rather more interesting.

Die hierin geäußerten Ansichten und Meinungen stellen nicht notwendigerweise die in anderen Mitteilungen, Strategien oder Fonds von Schroders oder anderen Marktteilnehmern ausgedrückten oder aufgeführten Ansichten dar.

Der Beitrag wurde am 06.09.17 auch auf schroders.com veröffentlicht.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: