Janus Henderson: Real rates matter more than inversion

An inverted US yield curve, with short-term interest rates higher than long-term ones, is seen as a recession warning. Janus Henderson’s Myron Scholes, Chief Investment Strategist, and Ash Alankar, Head of Global Asset Allocation, argue that monetary policymakers should worry more about the excess of yields over inflation.

09.10.2018 | 10:15 Uhr

Inverted thinking

“Our fugitive has been on the run for 90 minutes. Average footspeed over uneven ground barring injury is four miles an hour. That gives us a radius of six miles. What I want out of each and every one of you is a hard target search of every gas station, residence, warehouse, farmhouse, henhouse, outhouse or doghouse in that area. Checkpoints go up at 15 miles. Your fugitive’s name is Dr. Richard Kimble. Go get him”

Deputy US Marshal Samuel Gerard – whose portrayal earned Tommy Lee Jones an Oscar and a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor – may not have realised it but his first speech in the 1993 movie “The Fugitive” showed a keen appreciation of the Taylor series, a powerful and widely applied mathematical principle devised in the 18th century.

The Taylor series tells us that, in the search for clues as to what to do next, there’s no better place to begin than the start. When hunting a fugitive, the best strategy is to extend your search from the point at which he absconded by deducing how fast he may be traveling.

Members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) should heed this as they contemplate whether to keep raising US interest rates. The Federal Reserve (Fed) has bumped rates seven times since December 2015 and Fed funds futures predict further quarter-point increases in September and December this year. What is less clear is the path thereafter. The chances of a March 2019 hike fell further below 50 percent after the minutes of the last meeting were released on 23 August.

Three days earlier, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President and FOMC member Raphael Bostic said: “I will not vote for anything that will knowingly invert the curve.”

Inversion of the Treasury yield curve, where short-term yields are higher than those on longer-dated bonds, is “a powerful signal of recessions,” New York Fed President John Williams said earlier this year. Inversion has preceded every recession for the past 60 years, according to the San Francisco Fed, and the spread between two- and 10-year Treasury yields is now around 20 basis points, the tightest since 2007, immediately before the worst correction in 80 years.

Bostic and his FOMC colleagues are trying to judge the point at which rate hikes stifle growth. According to the Taylor series, though, not only is the shape of the yield curve ancillary to the real level of interest rates, inversion matters even less when volatility is low. With interest rate volatility as measured by the Merrill Lynch Option Volatility Estimate (MOVE) index hovering near record lows, policymakers should be even more firmly focused on the level of rates.

Rather than wondering whether the slope of the yield curve is dangerously flat, they should be asking whether the level of real rates, or interest minus inflation, is dangerously high or not, because that’s what matters to the real economy.

Homebuilders raising capital, for example, care if their borrowing costs in real terms are ten percent or one percent, not about nominal interest rates, because home prices should adjust for inflation. They care even less if the yield curve is flat or steep.

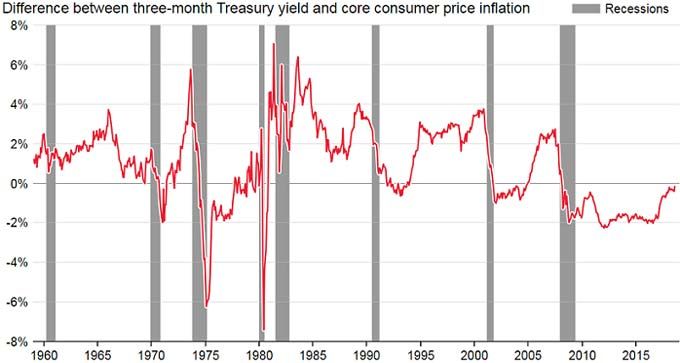

Since low real rates are stimulative, it stands to reason that, when real rates are high, financial conditions are tight and the risk of an ensuing recession is elevated. The chart below shows this empirically. The graph proxies the real rate by showing the difference between the three-month Treasury yield and core consumer price inflation.

Chart 1: real interest rates

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, data to August 2018; V. Flasseur | @Breakingviews

At the start of each recession over the past 50 years, real rates were not only positive, but they were well above zero – very different from today’s negative level.

While an inverted curve could suggest the market is pessimistic on growth and inflation, it may also simply be a symptomatic disappearance of the term premium, a function of monetary stimulus following the global financial crisis a decade ago.

Since the summer of 2016 the real rate, as proxied in the graph, has risen from minus two percent but remains negative, indicating that while the Fed has tightened conditions, they remain stimulative.

So, stopping rate hikes out of concern that the yield curve might invert may be exactly the wrong thing to do. Keeping real rates so low could ironically increase the chance of an inflationary style recession, forcing the Fed to quickly push up rates to control rapidly rising prices.

As it moves away from ultra-accommodative monetary policy, the Fed has to balance what the economy needs versus what it wants. That means focusing on the level of real interest rates first and the slope of the yield curve second. Monetary policy gift-giving continues in the form of exceptionally low and stimulative real rates. Prematurely ending rate normalisation may feed the recessionary risk the Fed wants to stamp out.

First published on Reuters Breakingviews on 13 September 2018.

https://www.breakingviews.com/features/guest-view-real-rates-matter-more-than-inversion/

Diesen Beitrag teilen: