NN IP: How will the Fed react to a changing inflation landscape?

Following the jump in US average earnings growth in January the perceived likelihood of what we would call the “inflation scenario” probably increased at the expense of a somewhat lower Goldilocks probability.

16.02.2018 | 12:19 Uhr

The recent equity market correction is probably mostly rooted in technical factors. Still that does not mean there is no fundamental story behind it. The key issue in this respect is how DM central banks will react to the macro and financial landscape going forward. When the policy rate hit the zero lower bound, DM central banks experimented with unconventional tools in an effort to drive real long yields below their equilibrium levels. The circumstantial evidence tells us that they were successful in this. DM growth rates have been clearly above potential for at least the past 1.5 years and there has been a melt-up in risk assets (even after the latest correction). As long as there is still clear evidence of slack in the economy and the risk rally remains moderate, this policy stance will be relatively undisputed. However, things become less clear once the unemployment rate falls to historically low levels and risk premiums on many assets fall well below long-run averages. Clearly, these issues are most pressing in the US right now, as Europe still has a lot of slack and a much higher equity risk premium. At the same time, US inflation has hovered well below target over the past few years which may have caused some downward slippage in inflation expectations. As a result, the Fed faces a trade-off between the need to firmly anchor inflation expectations, on the one hand, and the risk of overheating in the real and/or financial spheres, on the other.

One of the key lessons in economics is that trade-offs will become less sharp if you manage to ease some of the constraints. Applying this to the Fed’s trade-off we can say that on the real side there is a non-negligible risk that it is less sharp than it appears, i.e. there could be more room for GDP to expand before hard supply side constraints will be hit than the Fed believes. There is an interesting dichotomy between the labour market data (which suggest full employment) and the deviation from the long-run trend in GDP per capita (which suggests there is still slack). The lynchpin between these two is underlying productivity growth. If the latter accelerates, it will raise GDP growth per capita and slow down the fall in the unemployment rate. Even after the January reading on average hourly earnings we retain our view that the US economy can probably sustain an unemployment rate which is well below 4% for some time before core inflation rises substantially and persistently above 2%.

Meanwhile, in the financial sphere the important point to make is that periods of high volatility and large drawdowns are more or less the inevitable price to be paid for having a highly developed financial system. This system ensures that, on average, savings are channelled to investments in a much more efficient way than a few decades ago. As long as the outlook for nominal growth is and remains strong, central banks should certainly not provide a put option against market declines. Instead, policymakers should focus on making the financial system and the real economy more resilient against big drawdowns in the market. One of the most important aspects here is to take measures that prevent excessive leverage and which limit contagion between the balance sheets of various sectors.

Markets trade on stories

The main takeaway from this is that the trade-off between inflation credibility and real/financial overheating risks is a potential recipe for volatility. The reason for this is that what matters for market pricing is investors’ perception of the underlying fundamentals in a probabilistic sense. Nobel Prize winner Robert Shiller phrased this by saying that the market is driven by stories. At any point in time there will be several stories which can be seen as sets of future fundamentals. A small change in the relative probabilities of these stories could have large consequences for asset prices, especially if this pertains to stories which are pretty different from each other. Until late January, the dominant story was clearly the Goldilocks outlook which combined strong growth, low inflation and only very gradual monetary policy tightening. The pressure for this to happen may have been building for some time as US inflation momentum improved and Fed speak had become more relaxed about lowflation risks.

The inflation scenario is a classical trigger for a market correction. The essential idea is that the Fed has fallen behind the curve because of which hard supply side constraints fuel a substantial acceleration in inflation. This then forces the Fed to accelerate the pace of hiking, which pushes up the entire path of expected future short rates. Meanwhile, expected future nominal growth will most likely be revised down because of which the whole cocktail is headwind for risky assets. The classic example is the 1994 bond market carnage which is special because this inflation scare (which went hand in hand with accelerated tightening) did not morph into a recession. The reason is probably that the economy had just come out of the early 1990’s recession. Imbalances were still limited in size and hard supply side constraints were not in sight, e.g. the unemployment rate was around 6.5%. Hence, market participants probably retained a fair degree of confidence that the expansion would continue. Bear in mind that the Fed was much more pre-emptive at the time than it is today. In 1994 the Fed believed that inflation expectations were still not sufficiently firmly anchored to the target. Hence, any hint of upward inflation pressures required a swift and decisive response to prevent inflation expectations from rising.

On other occasions, most notably in the 1970’s and 1980’s, the realization of an inflation scenario meant a full-blown recession and a meltdown in risky assets. What’s more, inflation is certainly not the only scenario which can cause a correction in risky assets. In fact, since the mid 1990’s inflation has not really been a problem anymore as inflation expectations became firmly anchored at first and got exposed to the risk of downward slippage over the past few years. Over the past 20 odd years, market corrections have been mostly triggered by the fact that at some point the dominant story in the market became the overvaluation of one or more asset classes.

How will the Fed react to all this?

What does all this teach us about the recent correction? The first lesson to take away is to be humble in our ability to predict where things go from here. In real time it is impossible to tell with any degree of certainty whether or not assets are really overvalued. Even more importantly, the relative probabilities of different stories in the market can easily change again on the back of data releases or other (political) news flow. Having said all that, we believe that the low level of equilibrium yields goes a long way in explaining the valuation of risky assets. What’s more, upside inflation risks may well be more muted than many market participants believe, even though we have certainly become more optimistic on the US inflation outlook over the past few months. Finally, and most importantly, we believe that the Fed (and most certainly the ECB and the BoJ) will travel much more slowly along the inflation credibility/overheating risks trade-off than markets seem to think.

Let’s for the sake of argument assume that core inflation indeed accelerates more than expected. The key question for markets is then how the Fed would react. The first thing to bear in mind is that Fed policymakers are quite content with their gradual but steady march towards a neutral stance amidst the three cross currents they face (strong growth/diminishing slack, below target inflation and easy financial conditions). Hence, we feel the Fed will only deviate from its current game plan if it produces a clear failure in terms of reaching its objectives, if the data start to point convincingly in the direction of a substantial change in the nominal growth trajectory and/or if an intellectual heavyweight with very different ideas is appointed in a senior position. In addition, the Fed has a tendency to respond to changes in the data with a lag. The reason is that there is always a risk that a change in the data flow will prove to be transitory. If the Fed responds to this, it may subsequently have to reverse course which will inject unnecessary volatility in the markets and reduce the Fed’s future ability to control the path of expected future policy rates. As a result, there is a clearly positive option value of waiting when the data change direction. The inevitable consequence of this is that the Fed will respond too late to turning points. A third important factor which will mute the Fed’s response to accelerating inflation is the fact that the FOMC would be more than happy to see a period in which inflation overshoots the target moderately. Over the past year the Fed has emphasized the symmetry of its 2% inflation target and FOMC members are toying with the idea of a temporary price level target when the zero lower bound is hit.

As a result, we believe the Fed will only accelerate the pace of tightening materially if core inflation rises well above 2% for at least 4-6 consecutive months. The chances of that happening this year are very low, but there may be other factors which will cause the Fed to accelerate a bit. US Congress agreed on a FY2018 spending bill which could boost spending by USD 300bn over the next two years. This could increase the fiscal boost from around 0.3pp of GDP (due to tax cuts) to somewhere in the 0.5-0.8 pp range, which is significant for an economy with an unemployment rate of 4.1%. For the Fed this will mean two things. First of all, for a given status of the inflation and financial conditions cross currents this will strengthen the growth/ slack cross current which may well tilt that balance in favour of 4 rate hikes this year. Secondly, this fiscal boost will further raise r-star and hence also the expected terminal rate of this hiking cycle. As a result of all this, the trend which started in September where the market gradually prices in more Fed hikes may well continue for a while.

In short, even if core inflation accelerates meaningfully and ends the year above 2%, this in itself would not cause the Fed to increase the pace of hiking. However, changes to the other cross currents could well have that effect. This brings us to the next interesting question. Suppose we see a persistent change for the worse in the financial conditions cross current, i.e. we are in for a further tightening of financial conditions. Could this be enough to stop the Fed from hiking or even reverse course? In our view it would take a really large and persistent tightening of financial conditions which materially weakens the growth outlook for this to happen. Of course, the Fed provided a pretty strong put against market sentiment deterioration back in 2015/16. This was because the Fed had little conventional ammunition to respond to a deteriorating outlook. Meanwhile, the hurdle for reverting to QE was high and politically contentious. In such circumstances it is clearly important to stop a potential negative feedback loop between growth momentum and financial conditions as soon as possible. The Fed was able to do this by significantly bringing down future hike expectations.

The situation only two years later is of course very different. The US and global economies benefit from a strong feedback loop between solid growth momentum, easy financial conditions and high levels of private confidence. Clearly, in such a world a Fed put is not what the doctor ordered as it could fuel risk appetite further and contribute to bubble risks in some market segments. To put things in perspective: Financial conditions are roughly back to where they were in late Q4’17 after they had been easing for about a year, despite three Fed hikes. There is thus no reason to presume that the recent tightening of financial conditions (even if sustained at current levels) will pose any threat to above potential growth and hence there is no need for the Fed to deviate from its game plan. In view of this, one can understand why the President of the NY Fed Dudley said the market correction so far is “small potatoes” while his colleague Kaplan stated that “having a little more volatility may be a healthy thing”. Of course, the speed with which this all happens is of the essence here, i.e. if equity markets are falling precipitously at the day of the March FOMC meeting, we will probably not get a rate hike. However, abstracting from that “if” will be steady as she goes. The simple summary of all this runs as follows: The Fed will respond to changes in FC if, and only if, they have large enough implications for the nominal growth outlook. The latter will always be the ultimate lens through which the Fed judges financial market developments.

Emerging markets: steady capital flow improvement

It is remarkable how well emerging markets so far have digested the changing Fed expectations and rising bond yields in the US and Europe. Even during the recent global sell-off, both EM equities and bonds hold up quite well. Chinese and Korean equities have struggled a bit and in hard-currency debt we have seen some spread widening, but overall much less action than you normally would expect in a risk-off environment driven by DM inflation concerns.

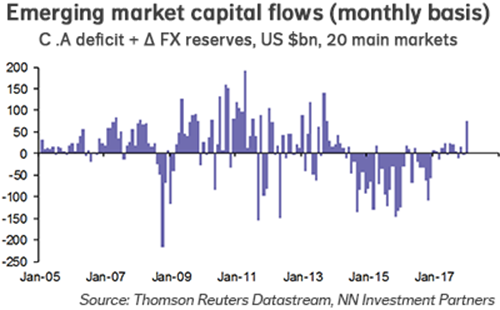

One explanation of EM resilience is the relatively benign Chinese macro picture, with stable growth and declining financial system risk. Another clear positive is the low and stable inflation throughout the emerging world, giving EM central banks room to cut rates or, in the worst case, to avoid hiking aggressively. These two points justify the steady improvement in broad EM capital flows over the past few quarters. The FX reserves and trade data reported for January tell that last January was the best month for broad EM capital flows since 2013, with an inflow of USD 73bn (see chart). From recent portfolio flow data we can deduct that February will be weaker probably, although non-speculative flows such as FDI can be expected to hold up well.

The steady improvement in capital flows and the benign inflation that is keeping EM monetary policy loose explain why our EM financial conditions indicator remains positive, with even some improvement in the past weeks. This is the main reason why we believe the EM domestic demand growth prospects remain good, despite some softening in EM growth momentum recently. In any case, EM credit growth ex-China continues to pick up, month after month.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: