Morgan Stanley IM: The Beijing Put — Stemming The Downward Spiral

Jitania Kandhari, Head of Macro and Thematic Research for the Emerging Markets Equity team, and Amay Hattangadi, Co-Lead of the Emerging Markets Core strategies, take a comprehensive look at China in the context of its recent stock market volatility.

21.04.2022 | 06:10 Uhr

Here you can find the complete article

In the early hours of March 28, China started a two-phase lockdown of Shanghai’s 26 million inhabitants1 in a desperate bid to control the spread of Omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus, in what is turning out to be the latest in a series of missteps that have stalked the world’s second-largest economy. China is currently facing its worst outbreak since the pandemic was first discovered in Wuhan in 2020.

The containment effort, which also has enveloped Shenzhen, and several other regions, as part of China’s “zero-Covid” policy, is the latest in a confluence of events --from regulatory crackdown on big tech companies, to delisting concerns over U.S. ADRs and increased geopolitical risk -- that have created a perfect storm for the Chinese markets.

Beijing’s ambiguous stance on the war in Ukraine has alarmed investors just as Xi Jinping’s policies promoting “common prosperity” (Display 1) and a barrage of regulations to rein in the tech industry have hurt their share prices. Government curbs on borrowing in the property sector also helped set off a spiral of falling home sales, surging corporate bond yields and eroded confidence among investors and home buyers. Allegations of Xinjiang human rights abuses have added to the complexity of investing in China for foreign investors, and in all likelihood this might be the toughest conundrum to resolve.

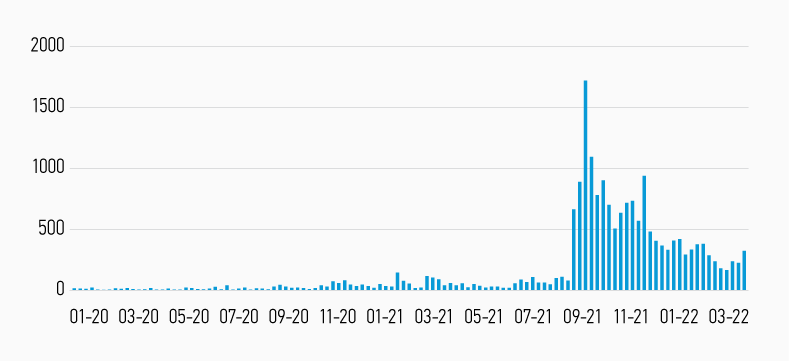

Display 1

Fading Mentions of “Common Prosperity”

Story Counts on Common Prosperity -Jan 2020 – March 2022

For investors, the Chinese markets were a roller-coaster ride. On the way up, stocks soared 87% from 2020 to record highs in early 2021, or almost doubling, before losing half their value in the following 12 months.2 The MSCI China Index is currently down 45%, recovering from a 55% plunge, from its early 2021 peaks.3 The regulatory crackdown on tech companies decimated their shares, as the listed market cap of Chinese Internet stocks collapsed almost 60% to $1.3 trillion, from a $3.04 trillion peak.4

The plummeting markets forced Beijing’s hand. Vice Premier Liu He, Xi’s top economic adviser, made a surprise policy change announcement on March 16 offering “concrete actions.”

Although vague on details, Liu downplayed the delisting of Chinese companies from U.S. exchanges and suggested plans related to ADRs and overseas listings were being worked out. He offered that the pace of regulation of Internet platforms should ease (Display 2) and the government would propose “strong and effective” policies to defuse the real estate sector and to keep the capital markets running smoothly . Investors liked the “Beijing put.” The Nasdaq Golden Dragon China Index jumped 33%, in one day, the most ever.5 Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index surged 9.1%, the most since 2008 while China's CSI 300 Index climbed 4.3%.6

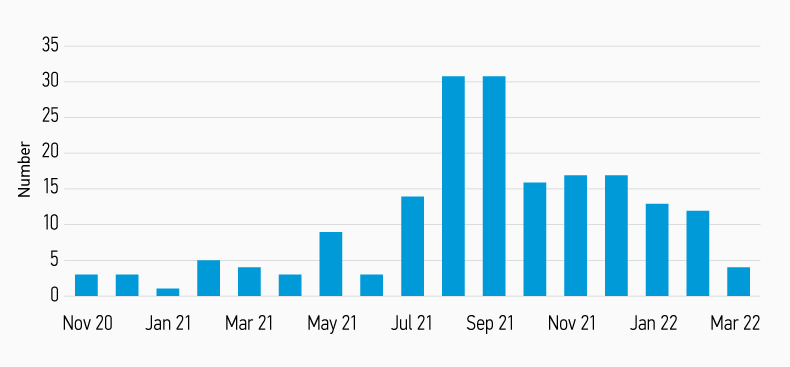

Display 2

China Could Be Past Peak Regulation

Beijing Regulatory Actions – November 2020 -March 2022

It is too early to say that China has witnessed its “Draghi moment.” A

decade ago, the European Central Bank president Mario Draghi staved off

financial calamity by promising to do “whatever it takes,” to save the

euro zone from a three-year sovereign debt crisis, in which several

periphery countries including Greece, Ireland and Spain had their debt

downgraded to junk status.

Government intervention can cut both ways. In the past, China’s handling of the economy was considered a success. This time, Beijing was forced to change course and appease international investors to head off further cratering of the economy. The government faced the risk of massive layoffs by Internet companies when employment numbers are already weak. The downward market spiral threatened to impact the real economy, necessitating a much larger stimulus later. Beijing also needed to send a signal regarding the debt-ridden property and construction sector, which could hurt the rest of the economy if not managed through orderly and controlled defaults. The final deciding factor may have been foreign investors pulling out of stocks and bonds in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to China Central Depository & Clearing, a depository for government bonds, overseas investors’ holdings of Chinese onshore bonds fell by 67 billion yuan (US$10.5 billion) in February, the largest monthly decline since 2017.7

China’s economy is slowing, weighed down by depopulation, declining productivity, high debt and the hollowing out of manufacturing industries. The country’s average income reached middle class phase in 2015, a point when all miracle economies have slowed.8 Mounting debts and a declining labor force have weighed on the economy which got a boost from last decade’s tech revolution. Today, the digital economy generates 40% of GDP output.9

Going forward, growth will likely increasingly come from the next generation of the new, “hard tech” driven economy. In the 2010s, China’s economy grew thanks to consumer Internet service giants that offered shopping, entertainment, mobile banking and the like. We believe the next turn will be to science-based industries like semiconductors, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, biotech and high-end manufacturing. Xi is pushing for self-reliance in tech, and less dependency on the U.S. in order to localize supply chains. His drive to make China carbon neutral signals deeper investment in industries such as electronic vehicles and renewable energy. If the 2000s saw the last surge of the Old China, and the 2010s the rise of New China, the 2020s will be the decade of China 3.0—an even more deeply digitizing economy.

Any stimulus will mean increasing debt in the economy, a concern given the degree of leverage in the property sector. Beijing, at this point wants to manage the situation with “talk” rather than large fiscal and monetary relief, which tended to prompt enormous enthusiasm from international investors. Therefore, expect more palliative rather than stimulative measures. While historically these may not address the core issues of slower economic growth and pressure on corporate earnings, in the current environment, it will help avoid a systemic risk induced by a sell-off in bonds and equities. In our opinion, the well-known “New China” names that dominated the market in the last decade will continue to fade. What excites us are the next generation science-based industries that will create world-class companies which will attract talent and generate well-paid jobs and steady earnings growth.

The wild card is the fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine. China must have been alarmed at how quickly the West unified to arm Ukraine, impose sanctions on Russia and isolate Vladimir Putin. The U.S. has publicly warned China that any attempt to help Russia evade the West’s sanctions would result in it being targeted with the same sorts of measures that have plunged the Russian economy into chaos.

Xi has called Putin his “best friend,” and although bilateral trade last year surged 35% to $147 billion,10 it’s hard to see Beijing taking any steps that could invite Western sanctions. The economic balance of power greatly favors China rather than Russia. China consumes 15% of Russia’s exports and provides about a quarter of its imports.11 Moscow has a much smaller trade influence, accounting for only 2% of China’s exports and supplying 3% of its imports.12 Today Beijing holds about $1 trillion in U.S. dollars, about 50% more than Russia’s total foreign currency reserves.13

For now, Liu’s intervention is a reminder that the government will not allow an economic downturn this year, especially ahead of the Communist Party congress that will reward Xi with an unprecedented third term. For his part, Xi would certainly prefer to arrive at the conference with an economy that is gathering steam and back on track. He faces a tough task trying to balance relations with Russia and the West, amidst a commodity price shock, a surging Omicron wave and an ongoing property fallout that will weigh on the markets.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: