Schroders: Pound devaluation - how the lessons of 1967 apply today

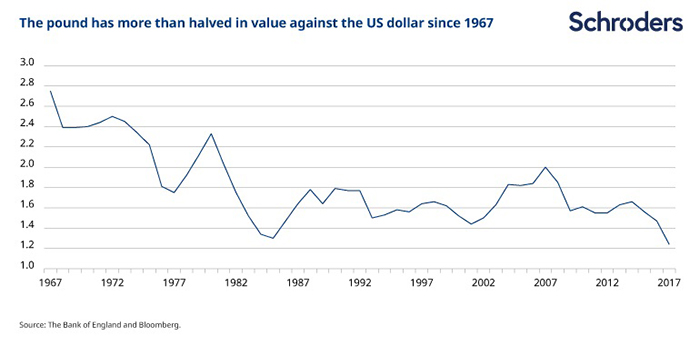

The UK actively devalued its currency in 1967, but the 20% fall in the pound since the Brexit vote continues a long-term trend of devaluation.

22.11.2017 | 10:53 Uhr

Since the UK voted to leave the European Union on 23 June 2016 the pound has devalued sharply.

It has fallen by as much as 21% against major currencies and has only strengthened against the Argentinian peso and the Turkish lira among emerging market currencies.

The UK has been here before. Anyone with a long memory may dimly remember this time 50 years ago as being particularly traumatic.

The 14% devaluation of the pound in November 1967 by then prime minister, Harold Wilson, was an admission of national failure that we might find hard to understand today after half a century of sterling gyrations.

The legacy of 1967

While Brexit may not be considered a devaluation in its truest sense, many of the problems Wilson had to contend with in the 1960s remain all too familiar – too many imports, not enough exports, and inflation.

Much like the devaluation of the pound since the Brexit vote, the legacy of Wilson’s devaluation was mixed at best.

Although not entirely attributable to the cut in the pound’s value, inflation nearly tripled between 1967 and 1970. And while devaluation did provide a short-term boost to the British economy, growth remained below the levels of the country’s international competitors.

Fast forward 50 years and the UK is experiencing many of the same issues. Inflation is again on the rise and the balance of payments - the value of imports compared to the value of exports - remains a problem.

But interest rates are a fraction of where they were in 1967. The lower exchange rates may also help offset some of the ill-effects of Brexit by keeping British businesses competitive and attractive to international buyers.

What does devaluation mean for investors?

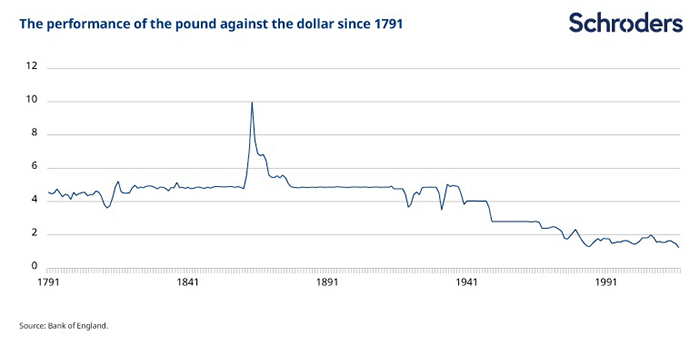

The devaluation of the pound is not a new phenomenon. At its peak in 1864, at the height of the US civil war, one pound was briefly worth $9.97.

Against other currencies, during certain periods, the pound would have been stronger. But in the main, against major currencies, the pound has been falling for a long time.

When the pound falls, the trade for an investor should be a simple one: buy British businesses with large international revenues. In theory, those types of businesses should benefit from a weaker pound because it makes their goods cheaper to export and their international revenues worth more once they are converted back into sterling.

That might have been the case 20 or 30 or 300 years ago, but in a globalised market the benefits of devaluation can be less clear.

For instance, how many parts used in British-made cars are imported from abroad? In other words, will the likely increase in sales abroad, due to a more competitive exchange rate, be offset by an increase in the cost of production because imported parts and labour become more expensive?

Also, the benefits of currency devaluation assume that companies reinvest profits in order to target new areas of growth and to increase production.

However, evidence suggests that business owners are instead focusing on cutting production costs and banking profits, instead of investing in the business and the workforce.

Keith Wade, Schroders Chief Economist, said:

“There had been hopes that the fall in the pound would help lift economic activity in the UK through stronger trade performance.

“However, alongside the complexities of international supply chains, many UK exporters are price takers in global markets with the result that the main benefit of the fall in the pound is felt through profit margins.

“As a result, there has been little evidence of stronger trade volumes since the Brexit vote, just as there was little response following the devaluation in the wake of the financial crisis.

“This effect has been seen in other countries such that the main impact of a devaluation is higher inflation rather than stronger growth.”

Net profit margins – the percentage of revenue left after all expenses have been deducted from sales – for FTSE 250 companies have risen on average by more than 300% over the last five years, according to Thomson Reuters data.

While this can be good for shareholders, providing those savings are redistributed in dividends or reinvested, it can have a more muted effect on the broader economy.

However, a falling currency can benefit a local stockmarket. Take the FTSE 100 Index for instance: two-thirds of its constituents generate their revenues overseas. That means they get paid in a foreign currency which, when converted back into sterling, is worth more.

It is similar if you invest in an international stockmarket. As a loose rule, if that market rises then as well as benefiting from the stockmarket returns, you should also benefit from any appreciation of the foreign currency. Returns will be paid in the foreign currency and will be worth more once converted back into your local currency, although some funds may hedge this currency risk.

Diversification, as ever, remains the key for investors to help minimise the risk of loss, preserve capital and generate returns.

Die hierin geäußerten Ansichten und Meinungen stellen nicht notwendigerweise die in anderen Mitteilungen, Strategien oder Fonds von Schroders oder anderen Marktteilnehmern ausgedrückten oder aufgeführten Ansichten dar. Der Beitrag wurde am 21.11.17 auch auf schroders.com veröffentlicht.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: