Janus Henderson: Debt build-up in debt collectors

The Corporate Credit Team at Janus Henderson Investors looks at some of the factors that are encouraging them to be cautious towards companies operating in the debt collection sector.

21.06.2018 | 14:06 Uhr

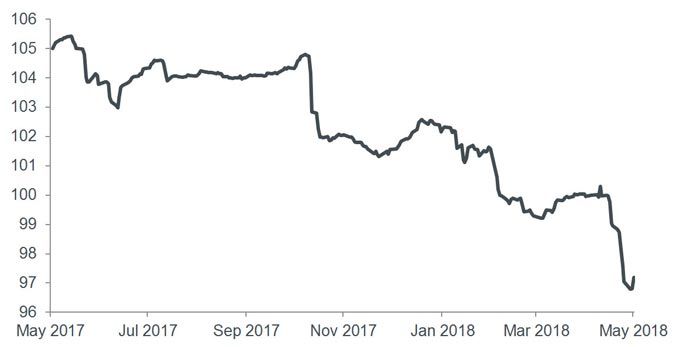

Debt collection companies buy receivables and non-performing loans – at a percentage of the debt’s nominal value – with a view to seeking to recover all or part of the original debt and make a profit. The sector has seen weakness in the past year with the price of bonds and equity of publicly-listed European debt collectors such as Arrow and Intrum trading at or close to 12-month lows (figure 1). Sentiment towards the sector among investors is varied, partly reflecting the large supply of bonds in the European high yield market. The debt collector sector has issued several billion euro worth of bonds over the last few years as the high yield market has supported the organic and inorganic growth of these businesses.

Figure 1: Arrow GBP 5.125% 2024 bond price

Source: Bloomberg, 31 May 2017 to 31 May 2018.

Past performance is not a guide to future performanceWe believe that a cautious approach towards the sector is warranted and the following are some of the key reasons behind this view.

High leverage

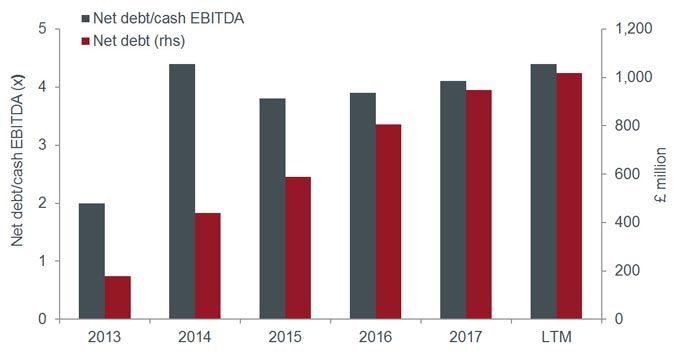

Leverage across debt collectors has increased materially over the past few years particularly through bond issuance in the high yield bond markets. For instance, Arrow has seen its leverage, as measured by its net debt/cash EBITDA* multiple, increase from 2x to 4.4x over the period from 2013 to 2018 (Figure 2). It is likely leverage will rise further as companies continue to engage in aggressive purchases of non-performing loan (NPL) portfolios and debt-funded acquisitions of servicing platforms. With IFRS 9, an International Financial Reporting Standard, impacting banks’ balance sheets, banks will be forced to sell their NPLs faster than previously. As a result there will continue to be a large supply of NPLs in the market – increasing the temptation for debt collectors to raise their exposure.*EBITDA = earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation

Figure 2: Arrow net debt over time

Source: Janus Henderson Investors’ calculations using Arrow company account data, LTM = last twelve months to 31 March 2018

Another example is Intrum, a Swedish debt collector agency. The company recently announced the acquisition of a €10.8bn non-performing loan (NPL) portfolio from Intesa Sanpaolo for approximately €3.1billion. This will increase leverage to 4.5x net debt/cash EBITDA, considerably above its 2.5-3.5x target. However, this excludes some of the off-balance sheet liabilities used to fund this transaction. Given the ambitious earnings per share growth targets the company has announced to its equity investors, combined with its acquisitive nature, it is highly likely that they will keep on investing aggressively in order to meet this target.

Limited cash flow generation

Cash flow generation across the sector is limited, with most debt collectors having free cash flow (FCF) as a percentage of gross debt in the low single digits. In fact, all of the main debt collectors have been FCF negative in the last few years because of their aggressive growth plans. For example, Lowell, a UK debt collector, currently generates FCF to net debt of just 2%. This effectively means it would take Lowell 50 years to pay down its debt from the cash flow it generates assuming returns do not deteriorate over this period.

Opaque accounting

Accounting methods used across the sector are to some extent ambiguous. For instance, expected remaining collections (ERC), which represents the expected future core collections of the portfolios, have a black box nature. This leaves management with a degree of discretion in recording the company’s ERC in its financial statements. Historically, most of these companies have forecasted ERC accurately, but they have also written up their ERC estimates. It is unclear how much of this write-up is driven by favourable market conditions versus improved collection techniques.Debt collectors mostly use EIR (effective interest rate) accounting, which makes it difficult to flag potential problems. Some also use off-balance sheet leverage for which there are no formal reporting requirements.Assessing the debt sustainability of debt collectors is difficult because the companies usually focus on “cash EBITDA” as opposed to EBITDA. The use of this accounting method masks the deterioration in underlying returns of the acquired portfolios.

Rating methodology

Optically, bonds issued by debt collectors look cheap relative to the ratings. However, we believe the methodology used by credit rating agencies to construct a view on a company’s ability to pay back debt and determine the likelihood of default can be flawed. Ratings on the sector often do not reflect the true fundamentals of the company or default risk. This can be seen in the case of Getback, a Polish debt collector, which defaulted on its Polish Zloty bonds in April 2018 despite being rated B, positive outlook, by S&P and B+, stable rating, by Fitch. Furthermore, Fitch only gave the inaugural B+ rating three months before the company defaulted. It appears that the reason for the default stemmed from Getback’s management overpaying for NPLs, which was not picked up by the rating agency methodology.

Senior management instability

The sector has seen significant turnover in senior management with high level departures at Intrum (CFO), Arrow (CEO and CFO) and Hoist (CEO and CFO). This high amount of turnover is worrying.

Pressure is building

Returns on portfolios owned by debt collectors are likely to remain under pressure as capital continues to enter the market, such as private equity and credit hedge funds, resulting in intense competition. This is already impacting Intrum: the company released disappointing earnings in Q4 2017, driven by lower earnings in their servicing division reportedly due to increased competition. In a bid to diversify and grow to remain competitive, we have also seen companies operating in the industry pay high multiples to acquire businesses. An intensification of competition could see this negative trend continuing.Increased regulation also remains a threat. The consumer element of debt collectors’ business models naturally attracts the attention of the UK financial services regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, which is concerned with the fair treatment of customers. Whilst we are not aware of any particular regulation initiatives from the FCA or their equivalent in other countries, the risk of an increase in regulation, which could increase the costs of collecting debt from consumers, remains real, particularly if the economic or political environment changes. For instance, the Italian coalition of Five Star Movement (M5S) and Lega (League) Party has proposed pushing through radical reforms across the debt collector sector.

Macroeconomic tailwinds have led to improved cash collections from customer and write-ups of expected remaining collections. An economic slowdown, however, could negatively impact cash collections. The high yield market has not really seen any of these businesses go through an economic downturn in their current form. While most of these businesses survived the 2009 crisis, they were considerably smaller in size and, more importantly, a lot less levered at that stage. For now, we are steering clear of lending to the sector as we do not want to have to step into their shoes and potentially have to chase up defaulters.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: