Janus Henderson: A "monetarist" perspective on current equity markets

Global economy slowdown is likely to extend and deepen, at least through mid-2019. A recovery in momentum is possible during the second half of the year but such a scenario requires confirmation from stronger monetary trends in early 2019.

09.01.2019 | 13:40 Uhr

In late 2016, the forecasting approach employed here – relying on monetary and cycle analysis – signalled that the global economy would grow strongly in 2017. A year ago, it suggested that a significant slowdown would unfold during 2018. The current message is that this slowdown is likely to extend and deepen, at least through mid-2019. A recovery in momentum is possible during the second half of the year but such a scenario requires confirmation from stronger monetary trends in early 2019.

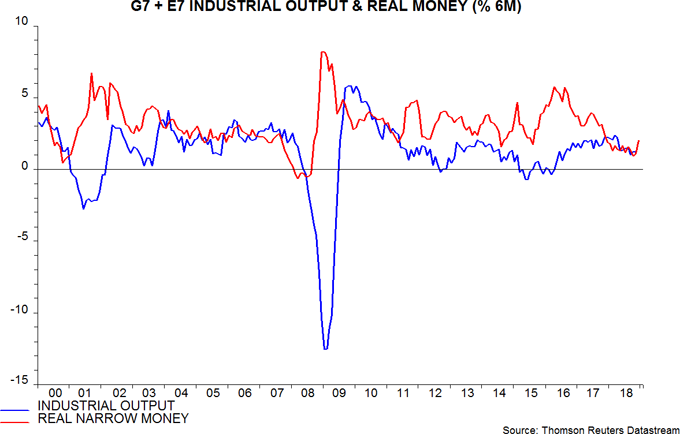

The forecasting approach utilises the “monetarist” rule that turning points in real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) money growth lead turning points in economic growth, typically by around nine months. The narrow M1 aggregate – comprising currency in circulation and demand or overnight deposits – has provided more reliable signals historically than broader money measures. Global six-month real narrow money growth peaked in June 2017, falling sharply through February 2018. Allowing for the usual nine-month lead, this suggested that six-month industrial output growth would peak around March 2018 and trend lower into the fourth quarter. This forecast has played out – see first chart.

Real narrow money growth moved sideways after February 2018 before falling to a new low in October. The latter development implies that the six-month rate of change of industrial output is unlikely to reach a trough until around July 2019 (or later), i.e. the current economic slowdown is expected to intensify during the first half of the year.

The forecasting approach focuses on the direction of real money growth rather than its level. It may, however, be significant that the October level of global real narrow money growth was the weakest since the 2008-09 recession and only slightly higher than the low reached before the 2001 recession. This suggests that the current global economic slowdown will be more severe than the previous two since the 2008-09 recession, in 2011-12 and 2015-16.

Real money growth appears to have recovered in November and December, raising the possibility of a revival in economic momentum later in 2019. The judgement here is that monetary trends need to strengthen further in early 2019 to warrant adopting such a turnaround as a central scenario. There are some grounds for optimism: Chinese monetary and fiscal policy easing is expected to lift money growth, while recent oil price weakness is curbing global inflation, supporting real money trends. A significant pick-up in global real narrow money growth, however, probably requires a Fed policy shift – at a minimum, a halt to interest rate rises and “quantitative tightening”.

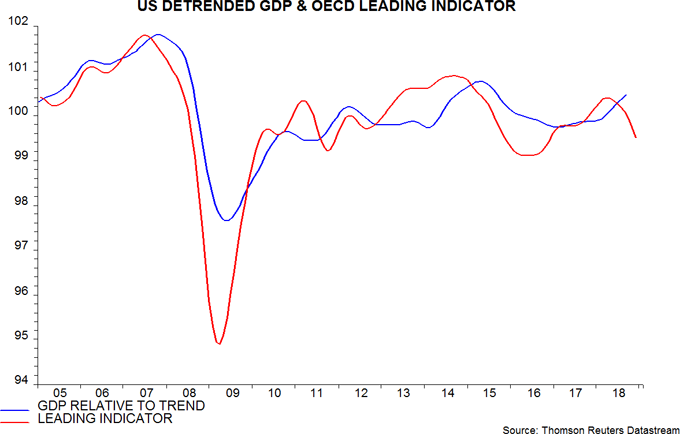

Supporting such a possibility, US money trends and other leading indicators suggest that US economic growth will undershoot Fed and consensus expectations in early 2019. Business narrow money holdings, in particular, have contracted in recent quarters, a development that historically has usually preceded a cut in business spending. A decline in the OECD’s US composite leading indicator, meanwhile, gathered pace through November 2018, implying below-trend and weakening GDP expansion – second chart.

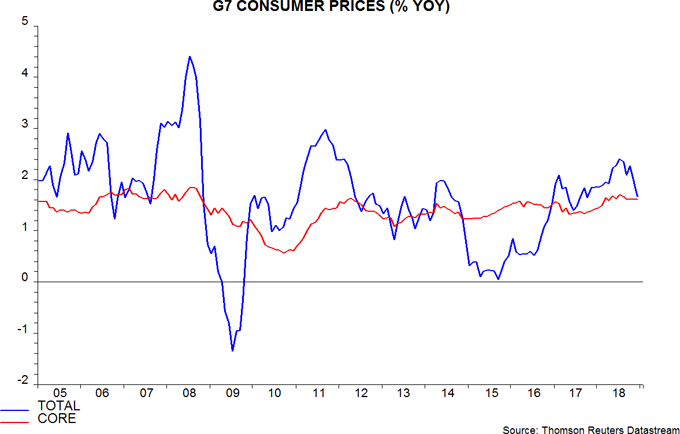

A rise in “core” inflation above 2% could, in theory, force the Fed to continue tightening despite an economic slowdown. US and global core inflation, however, has moved sideways recently, defying predictions of a pick-up in response to faster wage growth – third chart. With oil price weakness pushing down headline inflation, and slower economic growth likely to ease labour market pressures, wage rises may moderate during 2019. If not, restrictive monetary conditions suggest that profit margins, rather than core prices, will take the strain.

The cycles component of the forecasting approach attempts to place current economic developments within a longer-term framework and acts as a cross-check of the monetary signals. There are three key cycles: the stockbuilding or inventory cycle, which has averaged 3.5 years in length in recent decades (measured from trough to trough); the business investment cycle, which has averaged 8.5 years, with a maximum of 10.5 years; and a longer-term housing cycle, averaging about 18 years. The cycles are global, though have been dominated by US developments in recent decades, and shorter-term cycles “nest” within longer ones, in the sense that troughs tend to coincide. The three cycles reached simultaneous lows in 2009, explaining the severity of the 2008-09 recession.

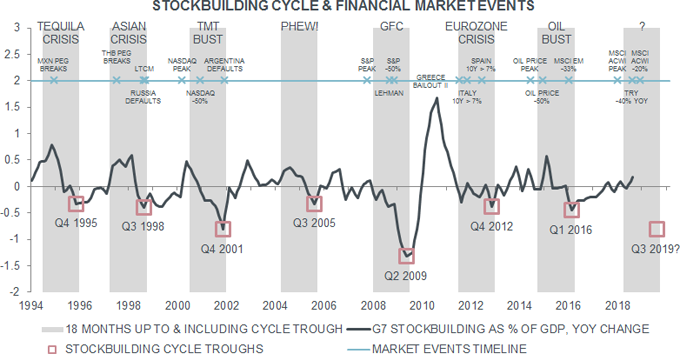

According to our cycle dating, the stockbuilding cycle reached subsequent lows in the fourth quarter of 2012 and the first quarter of 2016. The downswings into these lows contributed to the 2011-12 and 2015-16 global economic slowdowns. Based on the cycle’s 3.5 year average length, another trough could occur in the third quarter of 2019. A rise in stockbuilding during 2018 in G7 national accounts data is consistent with the cycle reaching a peak.

The difference from 2011-12 and 2015-16 is that the business investment cycle is also scheduled to enter a downswing. The last trough in this cycle coincided with a low in the stockbuilding cycle in the second quarter of 2009. With a maximum length in recent decades of 10.5 years, another trough is likely by the fourth quarter of 2019. The longer-term housing cycle, by contrast, is not scheduled to enter another downswing until the mid 2020s.

The stockbuilding and business investment cycles, therefore, are expected to exert a drag on global economic momentum during the first three quarters of 2019. A combined downswing would suggest a deeper economic slowdown than in 2011-12 and 2015-16, or even a mild recession – consistent with the message from monetary trends.

A reasonable working hypothesis is that both cycles will bottom out during the second half of 2019 and recover in 2020. The cycle analysis, that is, suggests that, if a recession is on the horizon, it is more likely to occur in 2019 than in 2020. The consensus view, by contrast, has been that any recession will be delayed until 2020-21 – in a September survey of US business economists, only 10% expected a contraction to begin in 2019, with 56% favouring 2020 and 33% 2021.

The consensus view appears to be informed partly by the observation that the US Treasury yield curve – i.e. the spread between the 10-year and two-year yields – inverted well in advance of most post-war recessions but has yet to do so. The current global economic slowdown, however, originated in China / Asia and spread to Europe, with spill-over to the US only now beginning. The Chinese government bond yield curve inverted in 2017, with a maximum negative spread in June of that year, consistent with maximum economic weakness in late 2018 / early 2019. The Chinese curve normalised in 2018, suggesting that China / Asia will lead any global economic recovery later in 2019 or in 2020. The US yield curve may prove to be a late or lagging indicator on this occasion.

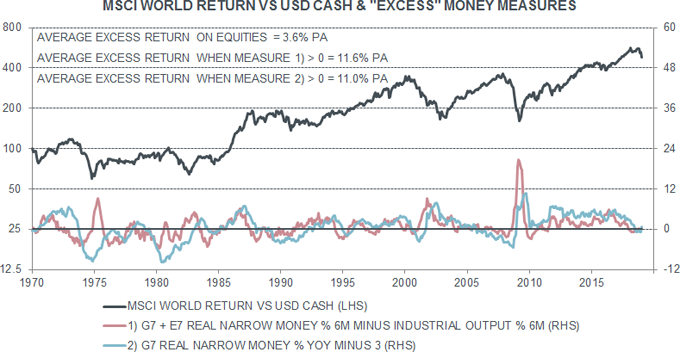

The approach to assessing equity market prospects here emphasises the concept of “excess” money, defined as a positive differential between actual monetary growth and the rate of increase required to support economic expansion. Excess money is associated with excess demand for financial assets at their prevailing prices, and consequent upward pressure on those prices. By contrast, a negative differential – “deficient” money – is associated with weak markets.

Excess money cannot be measured directly but our analysis indicates that two simple proxy indicators would have been informative about market prospects historically – the differential between global real narrow money growth and industrial output growth, and the differential between real money growth and its long-run average. These two indicators are shown in the fourth chart, along with an index measuring the cumulative return on global equities relative to US dollar cash.

Between 1970 and 2017, global equities outperformed cash by 3.6% a year on average. This outperformance was concentrated in periods when the excess money indicators were positive – the excess return averaged 11.0% per annum or more during these phases. Equities, by contrast, underperformed cash on average when the indicators were negative, signalling deficient money.

Both indicators were consistently positive between June 2011 and November 2017 but one or other was negative in every month in 2018. The indicators, that is, suggested lowering equity market exposure and adopting defensive strategies in 2018, and have yet to signal a reversal.

A further reason for a defensive stance discussed in previous commentaries is the historical relationship of market returns with the stockbuilding cycle. Equities and other risk assets have tended to weaken in the 18 months leading up to a cycle trough, with gains concentrated in the first 18 months of upswings. The fifth chart shows our suggested cycle dating and the implied 18-month “risk-off” periods for markets (shaded). Six of the last seven such periods were associated with a crisis and / or major bear market in one or more assets.

On the working assumption that the next trough in the stockbuilding cycle will occur in the third quarter of 2019, another of these risk-off periods started in early 2018 and is scheduled to last for another seven or eight months. The pattern of returns since early 2018 – both across asset classes and within equity markets – has been consistent with previous risk-off phases, e.g. defensive sectors and “quality” have outperformed, US equities have been relatively resilient, the US dollar has strengthened and credit spreads have widened.

This approach suggests preparing for a major turning point in markets in the second half of 2019, possibly the third quarter, assuming that first-half evidence on stockbuilding and business investment is sufficiently weak, consistent with the two cycles moving towards lows. Equities would start to recover later in 2019, with the pattern of returns in the risk-off phase reversing. Such a scenario would be expected to be preceded by a rise in global real narrow money growth in the first half of 2019, resulting in the excess money indicators described earlier turning positive.

An extension of recent market trends in the first half of 2019, that is, could create buying opportunities. The cycle analysis suggests that longer-term investors should use any recessionary repricing of markets to add to inflation hedges. Overarching the three cycles discussed earlier is a longer-term inflation cycle averaging about 54 years, with peaks occurring in the last century in 1920 and 1975, and another scheduled for 2027-29. The next economic upswing, expected here to be under way in 2020, may prove to be the most inflationary since the 1970s. The upswing is likely to begin with unemployment rates considerably lower than in previous recovery phases in recent decades, while demographic trends are expected to place upward pressure on economic demand relative to supply. The global banking system, meanwhile, may emerge relatively unscathed from the current slowdown, and healthy capital / liquidity positions could support much faster bank credit expansion in the next upswing, creating the monetary conditions for a sustained inflation rise.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: